Pros and Cons of the Japanese Public School System

Japanese schools have long been criticized for excessive use of rote learning and cookie-cutter output of students. But as Japanese society changes, its schools are changing too. Let’s take a look at what the schools here are doing well and at what we can do to supplement our children’s learning to foster their non-Japanese skills.

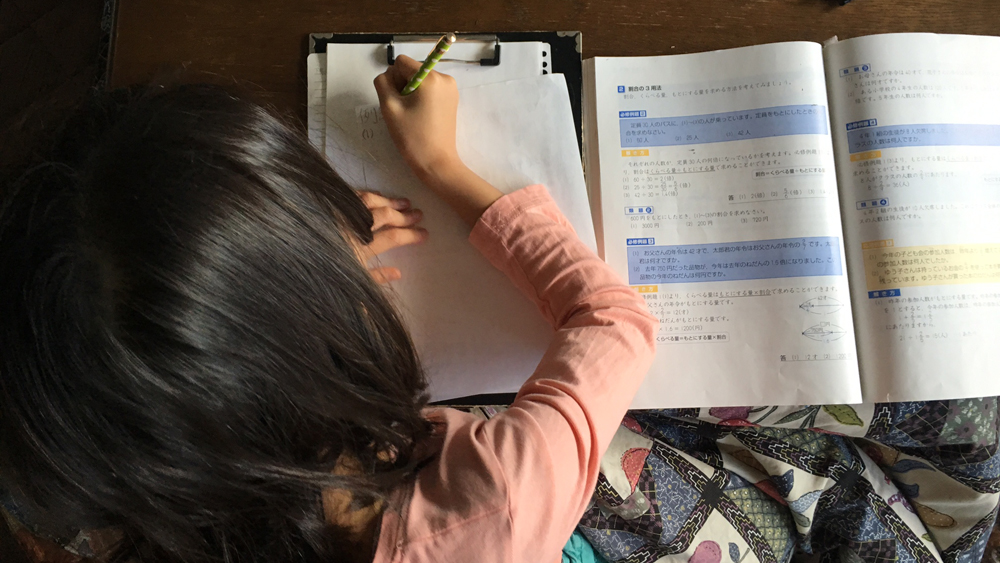

One clear advantage of putting your child into a Japanese public school is the acquisition of the Japanese language. On top of Japanese-language immersion of about six hours each school day, daily Japanese (kokugo) lessons will teach your child the Japanese alphabets (hiragana, katakana and romaji) and about 1,000 basic kanji (Chinese-style characters) over the six years of elementary school. If your child will be continuing her education at a Japanese school, she will require this knowledge. If she wishes to study at a Japanese university, entering via the Japanese school system will likely be the easiest route. Conversely, if your child wants to enter a foreign university, education via an international school is traditionally the easier approach, particularly in the junior high and high school years, as studies there are geared toward that goal.

The presence of the juku, or cram school, system here suggests if not an insufficiency in the Japanese education system, then at least a dislocation. The aim of juku is to get your child admitted to the best university he can enter, meaning getting more entrance test questions correct than his rivals. This doesn’t necessarily equate to learning, which is broader study that will help children live their lives effectively. Entering the best university has traditionally led to freedom of choice in the job market. As the number of children in Japan continues to fall, and companies here become increasingly desperate for consumers and for employees, Japanese corporations are shifting their focus to foreign markets. All this change seems to be loosening up traditional patterns in the job market and allowing some alternative routes to desirable jobs with Japanese firms. Considering the high level of education in Japan and the people’s respect of intelligence and knowledge, however, the overall desire for one’s child to receive a “top” education will likely damper flow-on changes in the education structure.

Time spent using Japanese steals time that could be spent using English, or another alternative language, consequently hampering its development. Help your children improve their English by exposing them to it as much as possible, of course in conversation at home and also with all media, including movies, music, game machines and the computer. Encourage a love of books by reading to your child from an early age, in English. Annual trips to see relatives back home will also help your child get into the habit of using English.

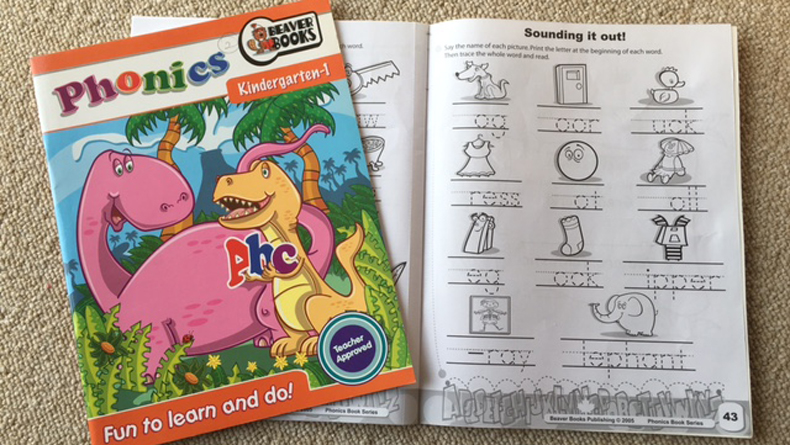

After my elder daughter learnt to read Japanese, she took to books like crazy. So I thought that if I can teach her how to read English, the rest would take care of itself. When she entered elementary school and I tried to teach her phonics, though, she just didn’t care—and of course I cared too much and every session ended in shouting. I think I should have introduced the phonics sooner. At the time though, I thought I should let her first grasp the basics of Japanese. Now however, as I watch my five-year-old copy katakana and English off the tissue box and then rejoice in being suddenly able to write the number five, I think kids are probably able to work it out even if everything gets thrown at them together.

Being older and somewhat wiser now with my second child, I will take the stress out of teaching phonics and reading by using some of the many programs offered for free on the internet. A search for “learn to read English kids” threw up many sites and apps, some free, some not. Even my ten-year-old enjoyed the YouTube version of the Endless Reader app.

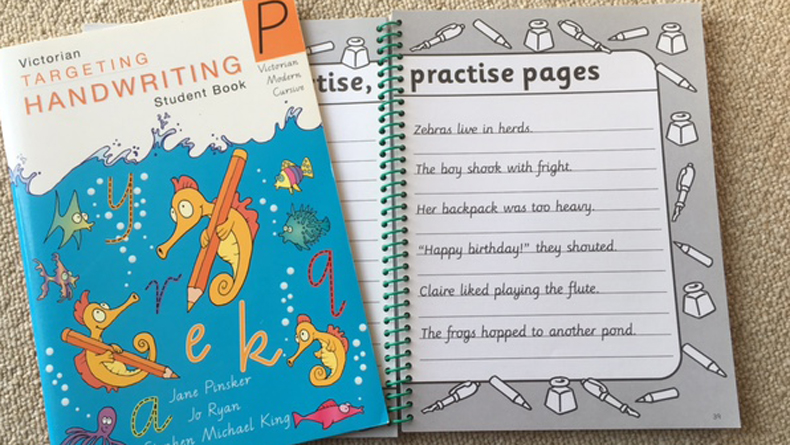

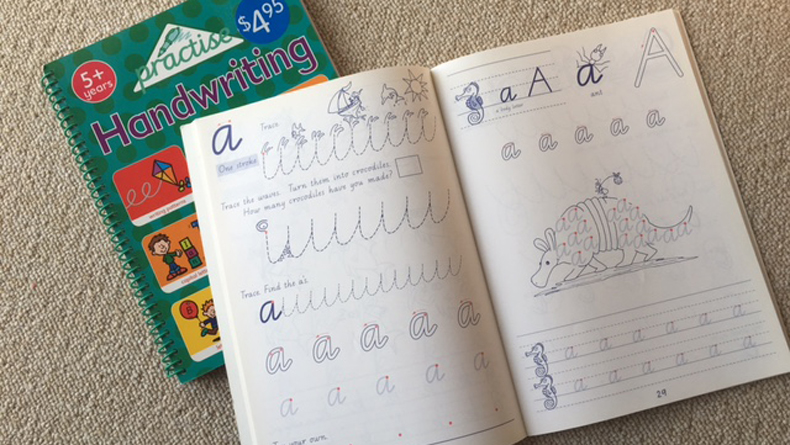

More traditional educational resources, like flash cards and workbooks, are also available for purchase over the internet. Home schooling resources are available online too, and of course offer not just a stop-gap for English language study but a complete, alternative method of schooling, albeit only for the brave.

Putting your child into English conversation classes can be difficult, not only because of the cost, but because native-speaking children can typically use much more English than other kids, but may not have sufficient reading and writing abilities to be able to take lessons with adults, making it extremely difficult to find an interesting class that will suitably advance their learning. Your child would probably learn more by studying (playing) at her own pace with an online English tool instead. If you are not in a hurry in regard to your children’s acquisition of English reading and writing skills, you can relax and let the kids learn them along with their classmates at junior high school.

The Japanese school system has changed somewhat in line with the external criticism that it has received. Although many of the parents of today’s elementary school kids will tell you they are unable to speak in front of a group of people, their children are getting used to it, with group presentations to the class now a common task at school, particularly in the first two years.

The computer room at my daughter’s school looks just the same as the one at my elementary school in Australia—and you know that’s an image from decades ago. Tablet computers do get used in public school classes here, but since there will be only four computers for use by a whole class, the kids will take turns in teams. Schools are not considered responsible for keeping children up-to-date with technology—that is something that happens at home.

Despite that exception, the public elementary school curriculum is thorough and comprehensive. My grade-four daughter’s class load includes science and social studies, art, English conversation and moral studies, as well as Japanese and math. In her physical education class, when practicing the parallel bar, or tetsubou, she and her classmates were given a list of various tetsubou moves and encouraged to try as many as possible and mark off the ones they achieved. There are so many more things you can do on the tetsubou than just rolling forward or backward! One could easily regard this as one of those uniquely Japanese phenomena that matters little in the larger world, but I think it is of great value in teaching children that if you try, if you practice, you can learn to do something that you previously couldn’t do. No matter what the subject, that is a lesson that is crucial for success in life and for healthy self-esteem.

Kids here are taught basic principles that they can then apply in later life. The teachers explain terminology and correct usage of tools and equipment to them. Singing in my daughters’ class is not simply singing. The teacher injects music theory, saying, “can you see that the pronunciation of this syllable here sounds better if it is done like this instead? This idea is called…”

A recent project in my daughter’s art class was to make characters out of small nails and blocks of wood. Instruction began with “this is a hammer and this is a nail. Hit the nail like this and it will go in easily, tap it like this and you can bend it, and if you want to pull it out, use this tool like this.” This of course can be construed as not encouraging creativity, since all the kids have been asked to make the same thing, but compared to my elementary school art classes in Australia many moons ago, the kids here are learning a skill, whereas my classmates and I were asked to make things with abilities we already had.

The flipside of this enviable comprehensive instruction of the basics is that it consequently defines appropriate usage or method, and therefore also a “wrong” way to do things. Whereas in the West we identify ourselves as individuals and when we make mistakes we take it on the chin or laugh it off, in the Japanese psyche, one’s own mistakes can suggest failings of one’s parents and perhaps even community elders, so the stakes are much higher in any risk-taking undertaken by Japanese, consequently making it harder to do.

Many of the lingering criticisms of the Japanese public school system are of elements presented by the nature of Japanese culture and society. When I asked Brian Christian, the principal of The British School of Tokyo about the pros and cons of the Japanese school system, he offered this observation: “There may also be reason to ask questions about stereotyping in Japanese schools—as in Japanese society in general. If I was the parent of young girls, I might want to be reassured that they would be encouraged to grow expecting the same opportunities as their male classmates.”

Mr. Christian also noted a tendency toward rote learning, which seems a reasonable phenomenon in a country where kids have to learn about 2,000 basic-use kanji characters by the end of junior high school. He also spotted these concerns which, as individuals, there is perhaps little we can do to counter: inconsistency of teaching standards and large class sizes.

Putting your child into a Japanese public school will put your whole family into Japanese society and a network of local friends and contacts that will make living here more enjoyable. If your family is a dual-culture one, then teachings from Japanese schools will be tempered by your teachings at home and by visits overseas. This dual-culture experience teaches our children that society is not that same throughout the world and surely kindles empathy, understanding, curiosity, and open-mindedness. They will be well equipped to navigate the futures that await them.

Comments

Leave a Reply

Find the Right School for Your Child

Savvy's schools section offers information about various schools in the Tokyo area, from preschools to high schools. Browse the page to read about each school's unique facilities, curriculum and after-school activities.