Been There, Learnt That: Bullying Can Hurt So Much

Parents Share Their Stories … And Offer Advice

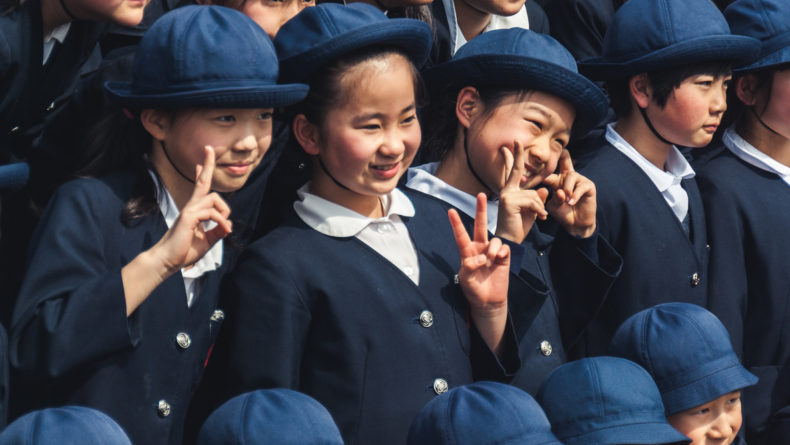

Bullying at school is a horrifying experience, especially when you live in a foreign country. Here are some personal stories from parents who have been there, learnt that about Japan’s ijime problem.

Something at school had clearly upset my fourth grader but it wasn’t until bedtime that I uncovered the source of her tears. During a regular changing of seating assignments in her classroom, a boy had remarked, “Oh, look, I ended up next to the kinpatsu no baka (blonde bimbo)!” My inner mama bear roared.

Aside from the fact that my daughter’s hair is brown, not blonde, this kind of teasing is something that virtually every bicultural child experiences. In a society still very much based on fitting in, our bicultural kids are easy targets for having skin and hair that might be a different color or texture, or for speaking more than one language.

It took several more weeks of gentle probing until my daughter finally revealed the name of the boy who had made the comment. Although it happened only once, it had clearly made my child miserable and I felt that the boy needed to know the weight behind those words. Fortunately, the classroom teacher was on board, too. She had a quiet word with the boy, who was genuinely surprised at the effect of his careless comment, and sorry for the trouble it had caused. He apologized to her, and I was happy with how it was resolved.

Bullying (iijme) and bicultural children is a common topic of discussion on social media groups for foreign parents in Japan. It is also alarming for parents when bicultural adults in the public frequently mention having been bullied as youngsters during media interviews.

Teasing Or Bullying?

Fortunately, my own three children have not been victims of bullying based on the fact that they are bicultural, although they have certainly been subject to teasing or othering (“the process of perceiving or portraying someone as fundamentally different”). However, I wouldn’t call the incident above with my daughter “bullying.”

In a society still very much based on fitting in, our bicultural kids are easy targets.

Bullying is typically characterized by repetitive actions that hurt the victim physically, and/or emotionally. It can be said that the group-oriented nature of the Japanese classroom, where conformity is still highly prized, can be a breeding ground for potential bullying. While there may be just a handful of ringleaders, other students, unwilling to risk drawing attention to themselves, may contribute to the problem by passively standing by and not attempting to help the victim.

Three Stories, Three Solutions

To help us understand the issue from a first-hand perspective, I asked three foreign mothers with kids in the Japanese education system to share their experience with bullying.

Jo Ebisujima, who helps other moms to organize their homes and launch and grow their businesses, was devastated when she realized that her first-grader son was being physically bullied by two classmates. In a blog post about the situation, she says, “I am standing there trying to stop myself from bursting into tears. Half of me wants to take him inside and never let him out again, the other half wants to go and show the bullies what it’s like being on the receiving end, which I know isn’t the answer but that is how I felt.”

Ebisujima and her husband approached the school and the class teacher notified the parents of the bullies, who apologized to Ebisujima’s son. However, when bullying behavior resurfaced a few weeks later, she and husband decided to take concrete steps to end it. This time they met with the principal, too.

Half of me wants to take him inside and never let him out again, the other half wants to go and show the bullies what it’s like being on the receiving end.

“They were actually happy that we, as parents had come forward to speak to them about it, and he (the principal) went on to say that often they don’t hear from the parents about what the child is saying or how they are acting at home,” she says.

Ebisujima showed them a short video about the effects of bullying. She was gratified to hear that the teachers re-enacted the contents for all the children at an assembly soon afterwards, and recommends the video to other families. As for her son, he is now a popular teenager. She adds that learning Aikido has also helped his confidence.

The other two stories come from the later grades in elementary school and junior high school years. This is the age group when bullying tends to peak in Japanese schools, before tailing off in high school. By this stage, bullying can move to a more sophisticated and devious level, making it harder for adults to spot. Moreover, victims are less likely to tell someone what is happening.

The summer her son was in 8th grade, TKN Mom* noticed he wasn’t going out to meet his soccer club friends but didn’t dwell on it at first. Her suspicions were aroused, however, when he didn’t know the details of games. After some probing, he revealed that a few boys in the team had been calling him derogatory names based on his appearance and excluding him from team meetings. They had been telling the coach that TKN Mom’s son was sick, but things eventually came to a head when the bullies falsely accused him of stealing a cell phone.

Once she knew what was going on, his mom took a proactive stance. “I called the teacher and then I visited the biggest bully’s mom and talked to her. The coach got involved and started to get to the truth of that cell phone incident, while I and the homeroom teacher organized a ‘foreigner’s visit’ to the school. I offered to answer any kind of questions in exchange for being able to ask some myself. My questions were mostly directed towards those bullies, and then afterwards the teacher took over and made it a cultural exchange lesson, about schools and bullying in other countries. My final step was an initiation for the bullies’ moms to my place for cake and coffee.”

Things eventually settled down, although TKN Mom’s son was no longer able to trust his teammates. Fortunately, he got a fresh start from high school and is now a well-adjusted young adult with a good job and busy social life, but there are some lingering after-effects of his ordeal. “I feel that he watches people before he decides to let them into his life,” TKN Mom explains. “For my son, it was important to know I’ll do everything possible to help, but never without his permission. Watch your child closely to notice changes in appearance, social life, and many other things. A mom will notice those changes, even very small ones.”

For my son, it was important to know I’ll do everything possible to help, but never without his permission.

Coincidentally, the final story also involves bullying among soccer club members. Diana reports that it began in fifth grade with her son being ignored, and then escalated in eighth and ninth grade. “In Junior High they were ignoring him, calling him ‘gaijin’, leaving notes on his desk that said ‘you are useless and should die’…. The soccer coach benched him and ignored him, setting the tone for his teammates to do the same.”

Unlike the first two stories, the school was unsupportive when Diana and her husband tried to broach the situation. “It was like talking to a stone. It lasted one year until my husband threatened to go to the police. By that time our son had quit school in year two of high school.”

After a child psychologist recommended changing her son’s environment, Diana tried a variety of avenues, including a farm stay in Japan, a homestay in Australia and an extended stay in her home country. She says that both her career and marriage suffered during this stressful period. Eventually, her son eased back into formal studies from high school and is now attending university. These days he finds a lot of enjoyment in music, which has opened up new opportunities and friendships.

Stay Strong, Keep Fighting

To anyone else who finds themselves in a similar situation, Diana’s advice is to stay strong and remain proactive. “As a non-Japanese be brave, assertive and fight for your child. I threatened to go to the press and the police, I demanded changes. Take a strong stand with your partner. Believe in your child and don’t buy into the ganbaru (“tough it out”) propaganda. Do not believe that there is only one way. It’s not true.”

“Let’s say the scales fell off my eyes. It changed me. Although I’m not aggressive, I don’t take the Japanese society crap anymore,” she says.

While I sincerely hope that nobody reading this article has to deal with bullying, these three moms have shown the importance of always being informed of what is going on and staying strong for your child.

*Pseudonyms are used to protect the respondents’ privacy.

Have you or your child ever had an experience with bullying? Share your story with us at editorial@gplusmedia.com or leave us a comment!

“Been There, Learnt That” is a monthly column in which Louise George Kittakadiscusses various issues she went through when raising her three children in Japan. If you have any questions for Louise on a topic related to raising bicultural children in or out of Japan, send us an email at editorial@gplusmedia.com or leave us a comment. Louise will answer your questions in her next article.