Boys Love, The Genre That Liberates Japanese Women To Create a World of Their Own

Tales of love between beautiful boys offer more than just double the eye candy

In a nation where patriarchy remains strong, Boys' Love homoerotic manga and other fictional media give women and girls a world of escapism from societal constraints.

Walk into the manga section of your local Japanese bookstore. The overwhelming images you’ll see are wide-eyed girls with impossible melon breasts. Even before a single word or picture is written, the assumption is clear. Girls exist to titillate men—whether they are characters, readers or the wider patriarchal society as a whole.

Now head to the part of the manga section furthest from the entrance. Here, you’ll see softer images of romance with titles for elementary school girls. Then, right near that, you’ll find the glossy covers featuring pretty boys—some of them closing in for a kiss. This is “boys’ love” (BL), a Japanese genre of manga, novels, anime, movies and now computer games. It features love relationships between young men but, surprisingly, is not made for a gay audience.

For A Female Audience

© Photo by iStock: maroke

© Photo by iStock: marokeThe boys’ love following in Japan is fierce but small. According to data from the Yano Research Institute, less than one percent of the population identifies themselves as BL fans, and the market earns only about one-twentieth of the overall domestic manga industry. Yet, despite being a minor one, the audience is solid.

Predominantly written by women, readers are also overwhelmingly female. BL is more than just double the eye candy, as these tales of romance between beautiful androgynous boys release women from a judgmental gaze and create a world that frees them from the constrictive social norms of reality.

Boys’ love is similar to the West’s slash fiction. Both depict homosexual relationships and emerged largely from amateur creations by fans. The majority of readers in both categories are women. However, most female fans of slash fiction identify as other than heterosexual.

In contrast, BL has some gay, bisexual and heterosexual male readers. Yet its fan base is predominantly heterosexual young women. Around 60 percent of them are aged between 15 and 29 years old.

Boy’s Love vs Yaoi

The Japanese genre is currently known by the katakana name ボーイズラブ (boizu rabu) or the abbreviation BL (ビー・エル). In the West however, it is still predominantly known by the older Japanese name of yaoi. This was the self-deprecating name that writers used back in the early days. It was derived from the initial sounds of the Japanese words “yamanashi ochinashi iminashi,” (山なし、落ちなし、意味なし), which means “no climax, no point, no meaning”—in other words, a really dull, dud of a manga.

Currently, in Japan, the two terms refer to different genres; boys’ love focuses on romance and is less extreme, while yaoi goes all the way with explicit sex scenes.

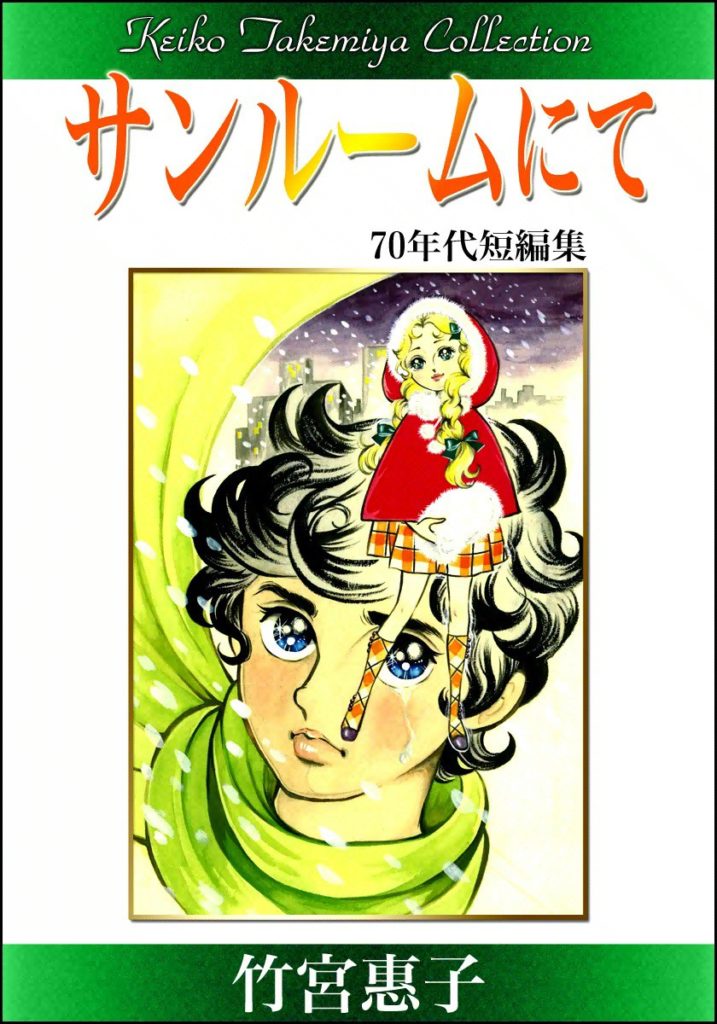

Breaking Into A Male World

The term “boys’ love” emerged in the early 1990s. However, the material began in the 1970s when female writers broke into the male-dominated world of manga for girls. Some started creating a genre of highly aesthetic depictions of relationships between boys. This was known as shonen ai, literally “boys’ love” in Japanese, and often referenced classical literature.

Amateur female writers then began creating subversive, sexualized parodies of mainstream anime and manga for boys. The male characters were recast as gay lovers.

“Rotten Girls”

As with many subcultures, a range of genre-specific words has developed. Key among boys’ love and yaoi is the word fujoshi (腐女子), used to describe female fans. This term takes the word for “women and girls” and changes the first kanji character to read as “rotten girls.”

The phrase emerged in the early 2000s among anime and gaming fans on the 2channel online community. At the time, 2channel was very popular in Japan. It was a self-deprecating label acknowledging how mainstream culture views women who enjoy imagining romantic relationships between men.

When discussing the coupling between characters, readers use specific terms. Uke (受け) means “to receive” and refers to the traditional female role, or “bottom” in modern English. Seme (攻め) means “to attack” and refers to the male role, or “top.”

Why Read BL?

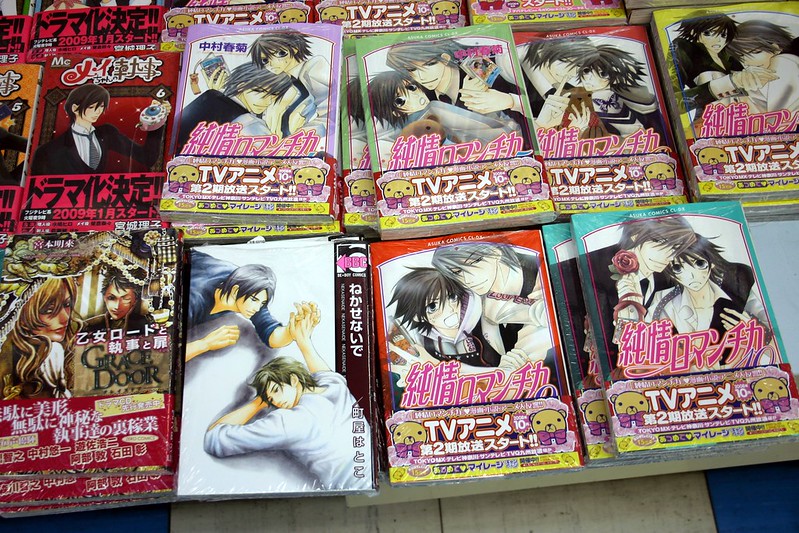

© Photo by Flickr: Timothy Takemoto

© Photo by Flickr: Timothy TakemotoOne Japanese female fan, a blogger who calls herself Ancha, says the greatest attraction of BL media is that readers can be part of a world that they can’t experience in real life and feel sensations that they wouldn’t otherwise feel. The obstacles to BL characters loving each other are much higher than in regular narratives. This makes the stories more romantic or “satisfyingly heartrending” for readers.

“For example,” Ancha writes on her webpage, “if the main character likes a boy but thinks he is straight, he will be fraught with doubt. He may wonder if it’s OK to like him or not. The greater difficulty for characters to get closer and reveal their feelings gives readers emotional excitement.”

Ancha began reading BL at about 12 years old and loved a BL version of Naruto. She says it is also exciting for women to read from the perspective of the seducer, or seme, as women are usually cast in the opposite role in real-world relationships. She also enjoys the absence of a female heroine in BL. In mainstream manga for girls, female characters are sometimes not relatable. The all-male lead cast of BL media makes it “stress-free,” she says.

It is stress-free reading because women don’t project themselves onto the male characters.

For characters to love each other despite heightened difficulty, including social resistance to homosexuality, inspires readers. Ancha describes this as “reverence for a pure love that ignores the judgments of others. BL is noble,” she says.

Beyond Judgment

© Photo by iStock: Kayocci

© Photo by iStock: KayocciBeing beyond judgment may be the ultimate attraction of BL. The way in which the genre developed shows professional female writers’ frustration with not being able to fully enter their chosen field, while fans’ creations show their thirst for boy-boy romance. Whether conscious or not, both reject the surrounding patriarchy in favor of a world of their own that they wish to enjoy uninterrupted by masculine demands and judgments.

Although the BL characters are men, the storylines are written according to women’s romantic desires and sensibilities. The characters have the heart of a girl in the body of a boy, which thoroughly removes any body shaming issues for readers.

Boy’s Love creates a world where women are not subjected to the judgments of men.

Beyond the pages, even, by labeling themselves “fujoshi,” BL fans prevent others from sticking a different label on them. With this subversive term, they voluntarily cut themselves off from the demands of the world of men, with “rotten” making it clear that they are no longer fit for male consumption.

Other Comments

A sub-genre of BL that depicts sexual relationships between older men and underage boys is commonly frowned upon, and gay rights activists have criticized BL for its inaccurate portrayals of homosexual men. Writers and fans, however, back up the genre by saying that the characters are not meant to represent real men anyway, and that separation—or escape—from reality is central to fans’ attraction to BL.

The academic world has also had much to say about boys’ love media, with most scholars praising it for aspects such as allowing readers to challenge fixed identities and explore alternative ways to navigate desire.

Rachel Matt Thorn, a cultural anthropologist at Kyoto Seika University, has described the appeal of BL among women of various industrialized nations as being based on “discontent with the standards of femininity to which they are expected to adhere, and a social environment that does not validate or sympathize with that discontent.” She sees its popularity as going hand in hand with the spread of “proto-feminist consciousness.”

Shared Goals

© Photo by Wiki Commons: Microsoft Bing Image Creator

© Photo by Wiki Commons: Microsoft Bing Image CreatorIntegral to Boy’s Love is its autonomy of female self-expression. (One manga writer has described the erotic yaoi media as providing a female alternative to conventional made-for-men pornography.) Freedom of female expression is an important step toward feminism. BL pushes that further by rejecting socially mandated gender roles. Its characters typically pursue shared goals in an equal partnership that breaks through the traditional male-female hierarchy.

BL media also offers a positive space for LGTBQ+ readers by creating fluidity in perceptions of gender and sexuality and resistance to the expectation of heterosexuality.

The genre, therefore, seems closely linked to two big social movements that have affected the world in the last few years—gender equality following the #MeToo movement and LGTBQ+ rights. But it is not wise to expect much social action from a subculture that revels in its separation from the real world and a readership characterized as tucking itself away in its bedroom to read.

It is reassuring, though, that when the petty ways of an unethical world get us down, Boy’s Love can perhaps help refresh our faith in the ideals of equality, mutual respect and freedom of identity. Sometimes, it may not be the Good Book that one needs, but a naughty one.

Have you read any Boy’s Love manga before? What did you think of it?

This article has been republished for 2024.

Leave a Reply