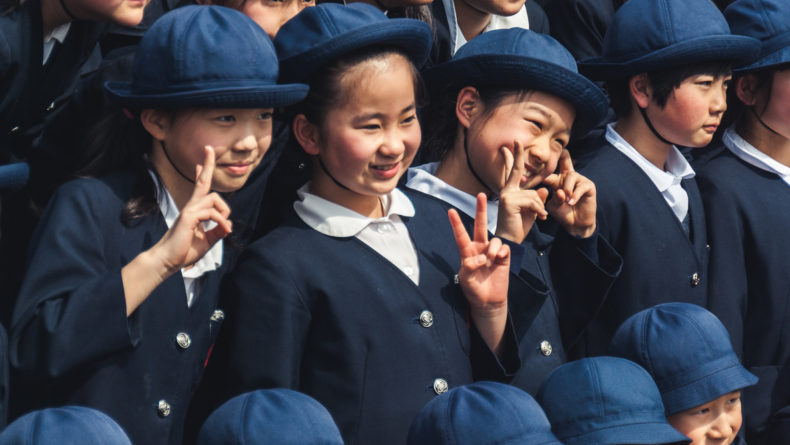

Been There, Learnt That: Raising Bilingual Children In Japan

Part I: The Early Years

What do you do when the option of sending your kids to an international school is non-existent and none of the recommended language development approaches really apply to your family? You get creative.

For those of us raising children from an international marriage, language development is an important issue. There are so many factors to take into consideration — do you expect to stay in Japan long-term? Will the child be educated in the Japanese or international system? Family moves, changes in parents’ work situations, new child-care/schooling arrangements and the arrival of siblings, can all affect the dynamics.

Three Kids, Two Languages

In our case, we have a Japanese dad, a Kiwi mom — and three kids. From the outset, our plans were to stay in Japan long-term and so we just assumed that when we had kids, we would educate them in the Japanese system. But, guess what? Life threw us a curveball when my husband’s company sent us to the U.S. and our two older children were born there. We returned to Japan when our son was four and our daughter was 18-months old, both speaking mostly English.

Although I didn’t appreciate it at the time, this was actually ideal in terms of giving them a real head start in English. As soon as my son entered Japanese kindergarten and his sister started going to a private nursery, they started acquiring Japanese as well. For my older daughter, in particular, it was a very natural process and her Japanese and English developed together. Within 18 months they could both chat quite happily with peers in either language.

Things changed again, however, when our third child arrived. She was born two months before her brother started Japanese elementary school and her sister “graduated” from her nursery school at the age of 3. I had been desperately trying to get my kids into licensed Japanese daycare (hoikuen), so I could work more. I was finally successful and my daughters gained places in the same daycare from that April.

My younger daughter’s language development, therefore, followed a very different path from that of her older siblings. Whereas the older two “started” in English, she did in Japanese. She was in Japanese daycare from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., four days a week, and by the time she was born, the older two were using mostly Japanese in their sibling conversations. I was tired with trying to balance work and the needs of my three little ones on a daily basis and it was often easier just to use Japanese with everyone.

But when she began speaking and I noticed a definite “Japanese pronunciation” in her English words, I panicked. I knew I had to make more of an effort.

Which Way Is Correct?

Though one of Japan’s best-known international schools happens to be in our area, the high cost of international school for three children meant it was never an option for our family. And would exposing them in an English-only environment mean that their Japanese would suffer later on? In fact, many Japanese parents of kids in international schools seem to be struggling with language issues. In a recent study, Makiko Kuramoto of Aoyama University interviewed Japanese mothers in international marriages about their family’s educational choices, and the result was that a third of those who chose international school reported struggling to maintain their children’s Japanese level, even while living in this country.

Many language experts recommend “One Parent, One Language” as a structured approach when raising bicultural children, whereby each parent speaks only their own language to the child. Another method I’ve been hearing about lately is “Minority Language at Home,” where, for example, the Japanese father and the foreign mother both speak English at home with the kids, if they live in Japan. However, I have to admit that our family’s situation was more of a “flying by the seat of our pants” approach at that stage!

So what do you do when the option of sending your kids to an international school is non-existent and none of the recommended approaches really apply to your family? You get creative.

Our Approach In The Early Years

Luckily, all of our children are fully bilingual now, and I can’t help but think that the following methods had much to do to make this happen. Here are a few of the things we did at home in the early years that I think helped the kids to acquire both languages at the same level.

Read, read, read: Well beyond the age when their peers would be reading for themselves, I read English books to my kids every evening. I staggered bedtimes and spent 20 to 30 minutes with each kid, one on one. It meant the bedtime routine could take up to 90 minutes, and there were evenings I longed to just slip quickly away and claim more time for myself. However, looking back now, I cherish the memories sitting on the bed with a child tucked into the crook of my arm, sharing the magic of a story.

English playgroup: I started a playgroup soon after returning from the USA as a way to meet and connect with other moms trying to use English with their kids. We met weekly to sing, dance, do crafts and read stories, and we had seasonal parties where older kids and fathers came. After four years, I passed on leadership to the next person—and I am thrilled that the group is still going! Some of my closest mom friends, Japanese and foreign alike, have come from this playgroup.

English Saturday school: Although mine didn’t, some playgroups metamorphose into so-called “Saturday schools” as kids get older. I was fortunate that my younger daughter was able to join one from 4th to 6th grade. Parents pool resources to hire a professional teacher to help kids work on English reading and writing.

Outsource: On a related note, it can be particularly effective to find someone else to teach your child if you want to add biliteracy—reading and writing—to bilingualism. I tried to incorporate some English reading and writing most evenings into our homework routine but it was tough when time (and tempers) were short. Having someone else work with your child even once a week can take the pressure off mom or dad.

Visits home: This isn’t practical for every international family, but regular visits home to see my parents were a big help. One of the incentives to work freelance was so that I could spend a month back home with my parents each summer. As it was winter in New Zealand and school was in session, I put the kids in local preschool, and later elementary and middle school, for several weeks, giving them a concentrated dose of English with kids their age. If you go home to summer, enrolling your kids in day camp or a community program is an option. (And if you stay in Japan over summer, consider a Japan-based program such as English Adventure.)

Media: Sneak in as much of the minority language as you can with TV, DVDs, online games, apps, and the like. Eventually kids will start to call the shots but when they are small and you control the content, make it count! And Skype makes it a cinch to stay in contact with overseas relatives for a language boost.

With the explosion in the nature of educational language programs, apps, and audiobooks, however, you may be wondering how much media is too much? I asked Adam Beck, a Hiroshima-based educator, dad of two bicultural kids and the man behind the informative and engaging Bilingual Monkey blog and The Bilingual Zoo online community, to comment:

“If technology is used mindfully, as supplemental exposure to more interactive input, this can certainly be beneficial. However, the risk in not proactively limiting the use of technology is that it can undercut the amount of time spent on richer, interactive language experiences between parent and child. When this happens, it makes the process of nurturing language development less effective. And ultimately, the more effective we can be in our choices and actions, in all ways, the more success we’ll experience over the length of childhood.”

Part II of this article will tackle bilingual education in the later years, from middle school onward.

“Been There, Learnt That” is a monthly column in which Louise George Kittaka discusses various issues she went through when raising her three children in Japan. If you have any questions for Louise on a topic related to raising bicultural children in or out of Japan, send us an e-mail at editorial@gplusmedia.com or leave us a comment. Louise will answer your questions in her next article.