A Look At Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s Womenomics 5 Years On

Japan's Gender Gap Is Still A Major Pressing Issue

The gender gap problem in Japan’s business and political sector remains real today, five years after Prime Minister Shinzo Abe launched his "Womenomics" initiative. What’s the problem here?

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s much ballyhooed targets for women achieving managerial positions in Japanese companies doesn’t seem to be working out as planned. What’s happening and how can Japan reverse the trend?

On the surface, the situation doesn’t look particularly bad: Japanese female labor participation surpasses the United States for the first time in history, according to data by the OECD. The Japanese government has set up incentive programs to subsidize companies that promote women’s participation in the workforce. Yuriko Koike became the first woman to be elected governor of Tokyo. Looking just at these “results,” you start believing that Abe’s Womenomics policies are going well, but a closer investigation reveals issues lurking below the surface.

“Womenomics”: The Master Plan

Womenomics is a term coined by Kathy Matsui, vice chair and chief Japan strategist at Goldman Sachs Japan, which refers to theories examining how the advancement of women in business and society links to increased development rates. In simple terms, countries where women have equal status in government, work and social standing, tend to do better economically. This also works with smaller-scale businesses. In results of a study done by the Catalyst group, companies with more women on their boards outperformed companies with exclusively male board members.

With Japan facing increasing economic pressure due to its aging population, one of the cornerstones of Abe’s financial growth strategy, Abenomics, has been creating policies to encourage more women to join the workforce, in order to jumpstart economic growth — a 15% growth in Japan’s GDP being the ultimate goal.

Nearly half of [Japan’s employed women in 2016] were employed part-time, on a contract base or as haken (temp) workers, which equates to low pay, little responsibility and few chances to advance their careers.

To achieve this, since assuming power in 2012, the ruling bloc has been trying to enact policies to improve the situation for working women in Japan, with the goal of — in Abe’s own words at the Global Summit of Women in Tokyo this year — creating “a society where women can shine.” Some of the main pillars of these policies are improving the availability of childcare and parental leave, encouraging companies to promote more women and create better working environments, as well as reviewing tax and social security systems.

Abe launched his Womenomics program ambitiously — or, some would argue, even recklessly. His initial goal was to have 30 percent of management positions in Japanese companies be held by women — well above the global average of 23 percent. However, due to a lack of progress in the private sector, in 2015 he was forced to lower those expectations to 15 percent for private companies and just seven percent for government-related jobs. What went wrong?

Growth in quantity, not quality

While the latest statistics released by Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare for fiscal 2016, show that Japanese women’s labor participation is indeed at a record high — 48.9 percent (a total of 28.01 million women), nearly half of them (13.67 million) were employed part-time, on a contract base or as haken (temp) workers, which equates to low pay, little responsibility and few chances to advance their careers.

New company employees are seen in the business district of Marunouchi, Tokyo.

One of the major reasons for the growth in non-full-time employment among women is the difficulty in arranging childcare (especially in larger cities), as Japan does not currently have enough nurseries to fill the demand. But another major reason is economic: The government offers large tax breaks for married couples where only one person works full time. A law set up in 1961 and so far left unchanged allows for ¥380,000 to be deducted from the taxable income of the head of a household if his or her partner earns ¥1.03 million or less per year. While families need additional income, the current regulations make it more profitable if one of the partners earns less than the other. Given the prevailing cultural belief that men are providers and women carers in Japan, this clearly becomes an easy decision for women to be the lower income provider at home.

Lack of clear incentives for the private sector

To further encourage female labor participation, in 2014, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare set up an incentive program to subsidize companies that promote women to senior positions. Under this program, companies who would hire women for managerial positions would receive subsidies going up to ¥300,000. This program had a ¥120 million budget and the ministry expected to receive around 400 applications, but in its first year, it received a grand total of … zero. A disappointing display, but not surprising considering how little economic difference the incentives would make — the subsidies were, after all, less than tax deductions for married couples.

One of the major reasons for lack of change in Japan’s corporate sector is the fact that the government has been merely encouraging businesses to comply rather than pushing them and hitting them where it hurts with legislation and economic sanctions. In other words, companies can easily ignore this new governmental request and hope it blows over. Firms acknowledge the need for change to deal with the increasingly disproportionate balance created by the country’s aging economy; however, in most cases, it is all talk and no action.

Top level hypocrisy?

Prime Minister Abe Shinzo (center) poses with (from left to right) Henryka Bochniarz, president of the Polish Confederation of Employment and chair of the 2016 Summit in Poland, Irene Natividad, president of the Global Summit of Women, Dang Thi Ngoc Thinh, vice president of Vietnam, Noriko Nakamura, chair of the Global Summit of Women in Tokyo, and Leni Robredo, vice president of the Philippines, at the Global Summit of Women in Tokyo 2017.

The saying goes that if you only tell people what to do without setting any examples yourself, you’re not getting any results and are at risk of being called a hypocrite. This is the stage that the Japanese government is finding itself in currently.

While Koike made history when she became the first female governor of Tokyo in 2016, the World Bank continues to rank Japan as one of the worst among wealthy countries regarding the number of female legislative representatives, with only 9.3 percent of parliamentary seats currently held by women. The country’s rankings in the Global Gender Gap are also continuing to drop, further three spots down since last year to 114th out of 144 countries in 2017 — the worst among the Group of Seven advanced nations.

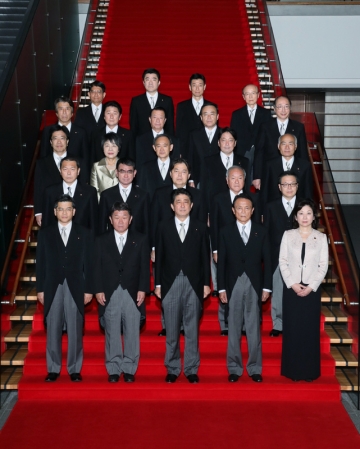

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s fourth cabinet inaugurated on Nov.1, 2017

Abe’s current cabinet is also an illustration of the drastic gender gap — there are only two women ministers out of 24. The Prime Minister also doesn’t have a single woman advisor, despite the pressing gender gap problem and his Womenomics policies. It isn’t a surprise that Japan ranks an embarrassing 165th out of 190 countries on the World Classification of Women in Parliaments index as of March 2017.

A call for change

Given Japan’s rigid immigration policies, it could be difficult, but one potential solution would be to import top-class managerial women from other countries. This could kickstart change and start nurturing a new generation of management-ready women who will hopefully also not accept the current 25.7 percent wage gap.

The stock phrase trotted out seems to be “Japan takes time to change,” but perhaps a more correct view is that Japan needs to be taken to the brink at gunpoint to adapt, and then the effect would spread rapidly. We see this historically, in politics, business and cultural adaptation.

The issue is much broader, though, encompassing the country’s social mores and work culture as a whole.

The government is currently focusing on employers as a solution for their gender inequality woes. The issue is much broader, though, encompassing the country’s social mores and work culture as a whole. When you see matahara (maternity harassment) rampant in companies and government, a work culture that praises those who work themselves to the edge of death and women with ambition overlooked and pigeonholed, it’s clear that drastic action is needed.

Even the optimistic Matsui acknowledges that there is still a lot of heavy lifting to do. At a recent talk organized by The Women’s Fellowship of Tokyo Union Church, she explained that one of the most important things needed to bring about change is to create an environment where peer pressure basically forces businesses to comply until it eventually becomes the norm.

The pressure needs to come both from the top and from within the ranks: women and men networking together to push back against staid, old management.

Leave a Reply