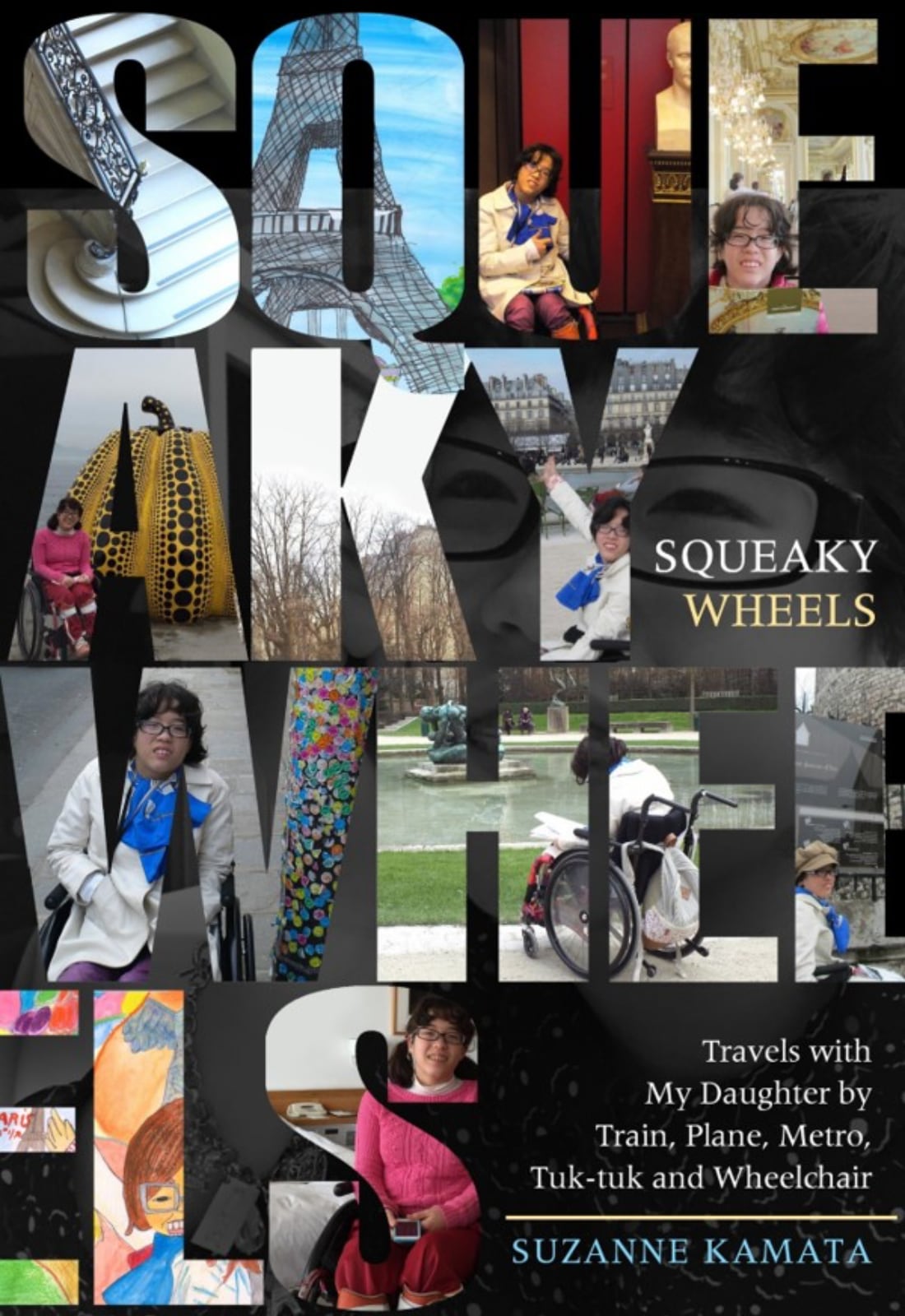

Squeaky Wheels: Suzanne Kamata On Her Mother-Daughter Travel Memoir

Have wheelchair, will travel! Mother-daughter trips are the inspiration for this new book

Vacations with a teenager in tow can be difficult enough, but when your daughter uses a wheelchair, it can be fraught with additional challenges. For Shikoku-based writer Suzanne Kamata, however, it has brought chances to witness her daughter’s burgeoning independence.

Suzanne is an American writer who has lived more than half of her life in Japan, spent entirely in Tokushima prefecture in Shikoku. She is the mother of girl-boy twins, now aged 20, and has published 12 books.

“Squeaky Wheels is about traveling with my bicultural teenage daughter, who happens to have multiple disabilities, as she is deaf and has cerebral palsy, and so she needs a wheelchair to get around. She also has a couple of learning issues,” Suzanne explains.

Communication Challenges

Suzanne together with her daughter, Lilia.

As Lilia has been deaf since birth, her parents were faced with difficult decisions about the best way to communicate with their daughter early on. As they fully expected to raise and educate their children in Japan, they chose to communicate with Lilia through Japanese sign language. Getting a cochlear implant (a small electronic device that helps people perceive sound) when she was small means that Lilia can now hear to a certain degree. “She can lip-read a bit and understand things from context, but she still prefers sign language. Sometimes we text with each other in Japanese, too,” says Suzanne.

She points out that Lilia attended a special school for the deaf and so didn’t have much opportunity to learn English. “She is culturally Japanese and I am culturally American.”

If you just stay home, people will never see what changes need to be made. If you go out and try things, you’ll struggle but then you can then figure out what needs to be done,

Squeaky Wheels has been a memoir in the making for some years. Even before she had the idea of writing the book, Suzanne made notes about family trips, but it was a conversation when Lilia was 12 that was a turning point.

“She told me she wanted to go to Paris. I was working part-time and we didn’t have much money. It seemed like an impossible dream then,” recalls Suzanne. A self-admitted Francophile who spent a semester in France while in college, Suzanne thinks her own love for the French culture probably rubbed off on her daughter.

Taking Off

This was shortly after American writer Elizabeth Gilbert’s travel memoir Eat, Pray, Love had become an international bestseller. “I read that she got a massive book deal to get the money to travel, so I had the idea of also writing a book to get the money for Paris. I did shop it around a bit but didn’t get any bites then,” says Suzanne. “The next step was to apply for a grant from the Sustainable Arts Foundation, which is for artists and writers who are parents. I asked for money to travel to Paris with my daughter in order to write a book and I got it!”

Just in case you’re wondering about Suzanne’s son, he was invited to accompany his mother and sister on their European jaunt, but he was busy with his baseball team and declined, so a girl’s trip it was.

“After this, I realized that Lilia was a fun travel companion and I took her on trips to the islands of the Setonaikai (Japan’s Inland Sea), so this was the impetus to do something I’d wanted to do for a long time.” The pair made several trips to see the stunning art exhibits scattered around islands in the Inland Sea.

“She’s always enjoyed drawing and she loves manga. I encouraged her to keep a picture diary when we were traveling around and to create artwork that we could use in the book, and some of this ended up being on the cover,” Suzanne notes.

“She’s always enjoyed drawing and she loves manga. I encouraged her to keep a picture diary when we were traveling around and to create artwork that we could use in the book, and some of this ended up being on the cover,” Suzanne notes.

Lilia has since graduated from high school and now resides in a group residence in Kyoto, where she is enjoying learning how to live independently—a decision she made for herself. She has also made new connections after joining a group for deaf young adults. With her son now attending college in Tohoku, Suzanne is entering a new phase of life.

“My kids are kind of used to being the subject of my writing—for better or for worse,” she says with a smile. “I often use their experiences or funny things that they said or did. But I’ve become more conscious of asking them for their permission, and the older they got, the less I’ve written about them.”

“This might be the last book I write about my daughter,” Suzanne says pragmatically. “But for me, it seemed like an important topic and it was a way for her dream to come true. Parts of it were also translated into Japanese and published here and there. She was very pleased! I don’t know if she exactly gets that people around the world are reading about her, though.”

Accessibility for All

Suzanne isn’t interested in attempts to label her as “this heroic mother” and hopes that readers will see beyond stereotypes. “When I was writing this book I didn’t want it to be an inspirational story per se; I wanted it to be about a teen daughter and her mother, and show the ways in which we are typical,” she points out. “Like how she doesn’t always listen to me, how we had arguments over her packing, and how she doesn’t always get out of bed in the morning or want to do some of the activities. I can remember having these same arguments with my mother!”

If money were no object, Suzanne’s dream trip with Lilia would be Scandinavia, which she says has a good reputation for making things accessible to people with disabilities.

When I was writing this book I didn’t want it to be an inspirational story per se; I wanted it to be about a teen daughter and her mother, and show the ways in which we are typical,

She acknowledges that Japan has also made considerable progress in the years since she first came here. “Then, I didn’t see people out and about in wheelchairs very often, but now I do. A big new shopping mall was built near our house and it has a lot of accessible parking spaces. I’ve noticed that all the spaces are occupied by cars with disabled stickers, so that is good that people feel more comfortable going out,” she says. “Smartphones, iPads, and other technology have been great, too! My daughter used an iPad in school and she uses sign language on Skype to chat with her friends in Tokushima and one in Spain.”

Even so, there is still room for improvement. On recent travels around the Kansai area, for instance, Suzanne and Lilia came up against some obstacles at major tourist attractions. “Sometimes I am still stunned,” Suzanne admits. “The most popular new attraction at a big international theme park wasn’t accessible to wheelchair users. And at a movie studio park, we wanted to have Lilia dressed up as a maiko (apprentice geisha) but they just said, ‘No wheelchairs’. Perhaps it was because the makeup station was on a pedestal, or maybe they thought it would be hard to dress her in a kimono. Whatever the reason, they were very unapologetic about it.”

In Japan, you are meant to gaman (put up with things) and not ask for help, but just like the title of my book, ‘the squeaky wheel gets the grease’! You have to ask. Until you mention something, people often just don’t know how to help.

Suzanne points out that some people think accessibility is doing a favor to those with disabilities—as if it’s optional—but she wants to see it considered as a right.

In closing, she shared some thoughts for other parents raising children with disabilities in Japan. “If you just stay home, people will never see what changes need to be made. If you go out and try things, you’ll struggle but then you can then figure out what needs to be done,” she says.

“In Japan, you are meant to gaman (put up with things) and not ask for help, but just like the title of my book, ‘the squeaky wheel gets the grease’!” she grins. “You have to ask. Until you mention something, people often just don’t know how to help.”

Read more about Suzanne and Lilia’s travels in her book, Squeaky Wheels: Travels With My Daughter by Train, Metro, Tuk-tuk and Wheelchair

Leave a Reply