What does living mean to you #1?

An interview with artist Hiroshi Sugimoto

As people’s lifestyles have become more diverse, the ways we live are also changing drastically. MORI LIVING has launched a new series interviewing various prominent figures about their ideas of “living” which encompass ideas of “home” “life-style” and “livelihood.”

The first edition welcomes Hiroshi Sugimoto, the world-renowned contemporary artist, who had a solo exhibition at the MORI ART MUSEUM in 2005.

His living room is beyond what we normally think of as a living room. It is a vast space consisting of 14 tatami mats plus a 2 tatami mat alcove and flooring with offcuts of Yakusugi, a type of Japanese cedar from Yakushima Island.

Space by the window is a step lower than the tatami platform, tiled to symbolize a dewy path of Roji, the garden path from the ordinary world to the world of tea. Guests put on Japanese Zori sandals here before going onto the balcony through a sliding glass door.

On the balcony, lead by the Nobedan stone path and stepping stones, edged with hedges and trees, stands the Tsukubai basin. We learn that the whole space embodies the concept of the teahouse and tea garden.

Sugimoto renovated a room of the 52 years old apartment himself into a space where the boundary between inner space and outer space is ambiguous. He calls it Uchi wa Soto or “Inside is Outside.” We could interpret this as “my house is outside.”

“Japanese people from ancient times have wished to die on a tatami mat. I do, too. So, tatami mats are essential for my living space. However, sitting on my legs is a pain and I thought of a way to incorporate tatami mats into our modern lifestyle,” he says.

He calls it Uchi wa Soto or “Inside is Outside.”

“I ended up designing the low table and stools at a similar eye level to when we sit on the floor. The alcove is also raised a little to meet our eye level. Inspired by when the US occupation army took over Japanese houses, walking in with shoes on and placing tables and chairs on the tatami mats, I call this Occupation Army Style,” says Sugimoto.

The table is made of two pieces of solid timber from an over 1000-year-old yellow cypress from Canada. With a fire pit built in the rear table, he can host and enjoy tea ceremony on chairs. The table legs are optical glass, which is a signature material for Sugimoto’s architectural projects.

“Living abroad for a long time, I’ve been invited to people’s houses a lot. To return the courtesy, I have to invite them as well. Having a place to be able to host people is the primary condition for my living space. My guests from overseas like tatami mats, the alcove, and the Roji garden,” he says.

“The space also needs to function as a meeting room for my artistic projects. My field of work has been expanding from photography to antique collection, producing Japanese traditional performing arts, and directing shows at l’Opéra in Paris this autumn,” he says.

My guests from overseas like tatami mats, the alcove, and the Roji garden […]

“And we sometimes rehearse dance or music performances here or have my Noh chant and dance lessons with private teachers. If I want, I can easily bring out reference books about antiques or architecture from my library in the next room,” he adds.

Though it may feel like there isn’t much of a sense of relaxation in this room, Sugimoto says “I wake up around 6 o’clock in the morning and am lost in thought in this room for a while. It’s important for an artist to have a time like that where you search for your vision with a clear mind without distraction because the daytime can be filled with miscellaneous tasks and I often dine with people in the evening.”

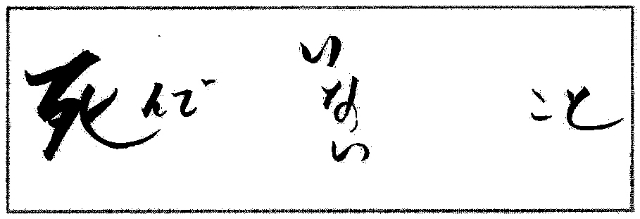

Q: What does living mean to you?

A: Not being dead

To our question – what is “living” to you, Sugimoto responded with a somewhat enigmatic phrase – not being dead. It can be interpreted that whether business meetings or spending time with friends, pursuing hobbies or solitary contemplation, every minute of our life is “living”.

He once said, “there are so many things I want to do that there is no time to die.”

This space must be what accommodates all the facets of his life in order to enhance his sense of living.

“Old Japanese wooden houses used to develop characteristics over the years and these were carried down from one generation to another. I wanted to seek a similar appreciation of the space in renovating apartments,” says, Sugimoto.

This is an ideal of living in a verticalized and highly specified metropolitan Tokyo home.

About Hiroshi Sugimoto

Born in Tokyo in 1948, Sugimoto moved to N.Y. in 1974 and started his carrier as a contemporary artist using photography. He established his architectural studio, New Material Research Laboratory, in 2008 and Odawara Art Foundation in 2009. In 2017, he founded Enoura Observatory, an integration of his antique and stone collections as well as an architectural insight. Works in various other projects including writing scripts and directing performances, landscaping, writing books and more.

This article originally appeared in Hills Life published by MORI LIVING. Text by Mari Matsubara, photos by Yasutomo Yebisu, edit by Kazumi Yamamoto and translation by Yuki Itai.

Leave a Reply