What Your Child Should Know Before Entering Japanese Elementary School

How To Prepare Your Little One For A Successful Transition To First Grade

Even if your child has spent their early years in Japanese daycare or preschool, the transition to primary school is a big one. Aside from the material preparation, like the purchasing of randoseru, there are several skills that will help them enter a new stage with confidence.

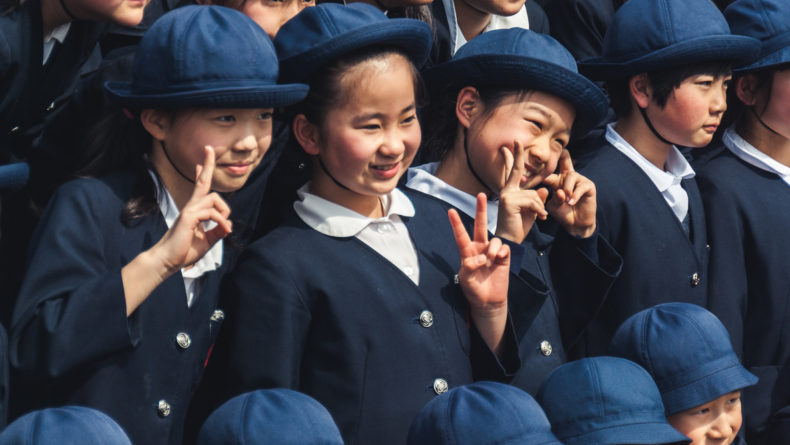

Starting first grade is one of the most exciting transition periods in a child’s life. Whether they attended daycare or preschool in Japan or abroad, or stayed at home with family, entering the elementary school system will ensure a springtime full of changes.

© Photo by iStock: yamasan

© Photo by iStock: yamasanWhat kind of changes, you might be wondering? Japanese children surveyed noted that the biggest differences between daycare or preschool and elementary school were the set time for lessons, the limited free time for play and rules on when to go to the bathroom or drink water and the amount of independence required of you. Compared to the expectations of schools elsewhere, this last point is particularly salient to the Japanese context. Indeed, in the last year of preschool (nen-chou gumi), teachers can be especially demanding on the five-six-year-old students in order to prepare them to be much more responsible for themselves the following year.

Having gone through a completely different North American school system myself, I was curious about these expectations for my little one, as perhaps you are as well after clicking on this article. So, after much reading and consulting senpai mamas, I narrowed the skills expected of the incoming first graders into three categories: academic, lifestyle routine and communication. I hope this eases some parent anxiety, as it has done for me.

Academic Skills

© Photo by iStock: nikoniko_happy

© Photo by iStock: nikoniko_happyThis is the first category, but it is also perhaps the most contentious. Ostensibly elementary school will teach the very skills I am going to list below. But, there are sometimes unsaid expectations going in.

Reading and Writing

One of those things is being able to read hiragana (and maybe katakana) and being able to write one’s name in hiragana. Yes, they will teach this in school. But, realistically, it is expected going in. At preschool, for example, although it is not always taught in class, many children exchange letters written in their own hand by ages four or five. Where did they learn then? Either at home or at juku (cram school) where the responsibility falls to parents to either contribute time or money to boost their children’s writing skills before entering elementary school.

Math

Similarly, but even more surprising to parents, is that it’s best to have a head start not only with counting but also with a little addition and subtraction. Maybe you’ve seen that the youji (young child) self-study books by companies like Gakken (4歳 たしざん 学研の幼児ワーク) and Kumon (はじめてのたしざん かず・けいさん 4) start teaching addition in books aimed at four-year-olds. As for counting, most books aimed at six-year-olds claim to teach proficiency up until 100 (6歳 かず 学研の幼児ワーク).

Life Skills and Routines

© Photo by iStock: MStudioImages

© Photo by iStock: MStudioImagesPerhaps the skills that are most emphasized by Japanese publications on this subject are those related to seikatsu shuukan (life skills and routines). In particular, it is often noted that getting your little one on an early to bed and rise schedule is essential since school starts at eight in the morning (unlike preschools which often begin at 10 a.m.) Also, in a Japanese school day, there can be multiple changes of outfits, to gym clothes, bathing suits, etc. As such, being able to dress oneself quickly, down to the smallest buttons, is an important lesson.

Similarly, being able to organize and pack one’s own things for the day is often emphasized. In the last year of preschool even, children are encouraged to be responsible for their items and entrusted with passing on certain messages and handouts to their parents. I wonder if this focus is related to Japanese kids’ commute, which is famously by foot in most cases. Since walking to and from school is a solo (or kid group only) affair, there is no adult present to make sure all of your things make it both ways. Training a young child to be responsible for their things is a big undertaking. But, with baby steps and some help, they can start to get organized. Why not support them by having clear/labeled spots at home where their school items can be stored? It can also be helpful to have a list of sorts at the door to help them remember what they need to do. Or try something like this cool magnetic board (Kutsuwa ME203 Metete Children’s Prep Board) to remind them what needs to go in their randoseru (school bag)!

Communication Skills

© Photo by iStock: Sasiistock

© Photo by iStock: SasiistockIn primary school in Japan, outside of international schools, Japanese fluency will obviously make your child’s life easier. However, language skills aside, there are specific forms of communication that can set your little one up for success as an ichinensei (first grader). One of these things is aisatsu (greetings). While important in all cultures, learning the proper aisatsu in Japanese and getting them to use said greetings will help them make friends and make a good impression at their elementary school.

While aisatsu is arguably more about teaching respect for the culture, community and individuals around, other communication skills are part of a starter pack for kids learning to be independent in the world and beginning to care for themselves. This is especially true as they are responsible for their own commute and are allowed more freedom of movement in parks. So, what are some important things that six to seven year olds should learn to say clearly?

- The ability to ask for help in various situations—some more scary than others: during natural disasters, getting lost, feeling threatened by another child or adult, forgetting a necessary item like their umbrella on a rainy day, etc.

- Being able to explain what is bothering them and/or what they need in Japanese is a life skill that many books say needs to be ingrained by first grade.

- Learning how to say how you feel is also key for a kid of this age. For this, they need both the vocabulary words as well as experience to correctly convey a feeling.

While I’m not suggesting that little ones be fully emotionally literate by elementary school, the ability to express themselves in a variety of situations can help keep your child safe and happy during this big transition.

Do you have a child in elementary school in Japan? Let us know what you think they need to know before first setting foot on the school grounds!

Leave a Reply