Been There, Learnt That: My Not So Brilliant Career As A PTA Yakuin

I Came, I Tried, And I Failed … In Order To Conquer

One foreign mom shares her experience with Japan’s PTAs and tips on how to cope with it.

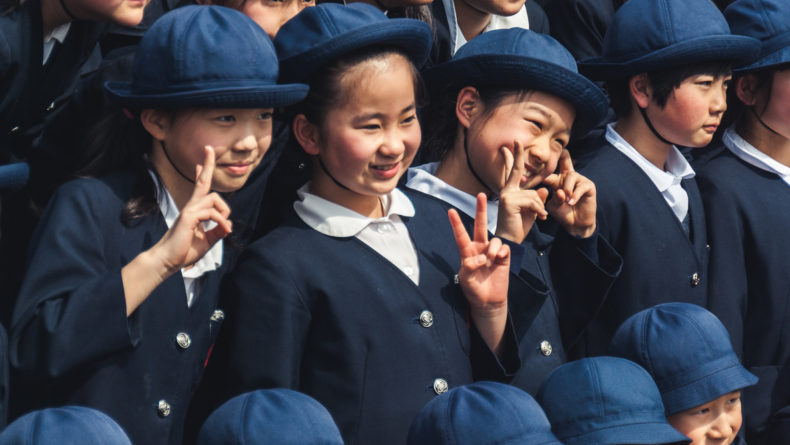

April brings excitement and trepidation in equal measures for families in the Japanese school system as children start new schools or move up to a new class. Then, a few days into the school term comes the first class meeting for parents. After everyone introduces themselves, the teacher announces, “So, who would like to volunteer for the school PTA this year?” A roomful of chatty parents is suddenly rendered silent as everyone begins earnestly contemplating their navels.

OK, I have tried to be politically correct by saying “parents,” but who am I kidding? Even in this day and age when increasing number of Japanese moms are in the workforce, the vast majority of the people at these class meetings are women. While acknowledging that some dads do occasionally attend meetings and do take on PTA officer duties, I am going to say “mothers,” since it’s still invariably seen as a woman’s role.

You might think it strange that Japan uses the very English-sounding term “PTA,” but it is actually no coincidence as the concept was borrowed from the American Parent-Teachers’ Association. It was introduced after World War II as a way to involve parents in the running of schools. While the concept might be Western, however, the PTA is a microclimate of Japanese society.

My PTA debut

I found this out the hard way after volunteering to be one of the PTA officers, or yakuin, when my oldest child started first grade in elementary school. I had no previous experience in this role whatsoever. My son had attended a Japanese kindergarten where there were three basic rules about being a PTA officer: You were excused if you were working, pregnant or already had a younger child. I always qualified in at least two of these areas.

Some schools have a variety of sub-yakuin who help with minor jobs, but at our school the three class officers had to do everything.

But things were about to change. You could have cut the air with a knife when during our first parents-teachers meeting, my son’s first grade teacher smiled brightly and asked, “Now, any volunteers for class yakuin for PTA this year?”

The teacher persisted. Indeed, she had no choice—she was duty-bound to produce three volunteers before she could end the meeting. If there were no volunteers, then we would have to revert to the time-honored method of drawing names from a hat—or perhaps a few rounds of the ever-popular janken (rock, paper, scissors).

Finally, finally one mother and then a second hesitantly raised their hands (two stay-at-home moms with just one child apiece, although I didn’t know it at the time). “It would be a great way to get to know the school and make some friends!” implored the teacher, desperate to fill her quota of three.

It was nearly 5 pm and I had my two little girls to pick up at daycare. Besides, I wanted to make some mom friends. I raised my hand. “Wonderful, thank you!” said the teacher, her face wreathed in smiles and the tension in the room evaporated as the other mothers visibly relaxed.

Bumpy Start

I had assumed that PTA meetings happen at night or on weekends, as they did back in my native New Zealand. Wrong! Monthly meetings were slap-bang in the middle of the morning on a weekday. I had a toddler, a three-month old baby, was working four days a week and leading a playgroup on the remaining weekday. I quickly realized I was way out of my depth.

Not only were there monthly meetings with the whole PTA, but yakuin were expected to arrange various things for their respective classes, such as get-togethers for the moms, a team for the “PTA Sports Day” and a roster of volunteers to come in once a week and read to the kids.

No two schools’ PTAs seem to be arranged quite the same way, even varying widely within the same town or city. Some schools have a variety of sub-yakuin who help with minor jobs, but at our school the three class officers had to do everything.

I also realized that my personality did not mesh well with the vibe at PTA meetings, where everyone—especially the newbies—seemed to be desperately striving to look diligent, always wary of how others were looking at them. Making suggestions such as, “Couldn’t we start at 9, for those of us who have to go to work afterwards?” that went against the status quo didn’t go down too well.

Surrender And Revival

After several miserable months I finally caved in and told the teacher I couldn’t cope any longer. At an embarrassing class meeting I admitted defeat and another mother stepped in.

But with the years, as I gained more knowledge on the ins and outs of Japan’s PTA, I also gained self-confidence. Aiming for a better second chance, I went on to volunteer again as yakuin for my two daughters’ classes, making sure it was at the same time as a Japanese friend both years. I can’t say it was a fun experience, but I somehow survived both years with my sanity intact.

Things improved for me on the PTA front at junior high school, where almost all the mothers were working and nobody had time to devote to earnest meetings in the middle of the day. A greater number took on PTA roles, sharing the load and allowing people to sign up for things that suited their interests and schedules.

In the long run it is probably better to be a team player, show up and offer to help out for one year.

As to me, I offered to write something for the school’s literary magazine—a no-brainer for a writer, and a task I could do from home. And in my younger daughter’s final year in junior high, I signed up to help run our class booth at the school bazaar. It had always irked me that I had to slog away at PTA stuff while my husband got off scot-free, but I finally realized my goal of getting him involved. The memory of him decked out in an apron and kerchief, selling churros at the bazaar, still makes me grin.

Tips For Successful Involvement With The Japanese PTA

- Don’t volunteer in your first year at a new school! Give yourself a grace period to see how the PTA works before jumping in headfirst.

- Some elementary schools keep the kids together for two years at a time, and if that is the case, I suggest volunteering in second or fourth grade, as you will be dealing with a known contingent of moms and kids.

- Volunteering in sixth grade is a whole new ballgame as the yakuin are usually expected to handle the extra duties surrounding graduation as well. Get involved only if you’re ready to be available 24/7.

- Planning ahead can pay off: One of my friends had never volunteered at our elementary school, and with her older child entering sixth grade, she was very anxious about being hit up for the graduation committee. So, before they could grab her, she loudly announced to everyone that she was volunteering for her fourth grade son’s class as yakuin.

- It might be possible to wriggle out of yakuin duty by playing the “I’m not Japanese” card, or just by not showing up to class meetings. However, at the end of the day, 99 percent of Japanese moms are just as reluctant to be yakuin as we foreigners. In the long run it is probably better to be a team player, show up and offer to help out for one year. If being a main yakuin is too hard, maybe there is a more minor role you can help out with, or sign up your partner for something!

“Been There, Learnt That” is a monthly column in which Louise George Kittaka discusses various issues she went through when raising her three children in Japan. If you have any questions for Louise on a topic related to raising bicultural children in or out of Japan, send us an e-mail at editorial@gplusmedia.com or leave us a comment. Louise will answer your questions in her next article.