Ladies & The Law: The Murder That Resulted in Japan’s Anti-Stalking Act

The Tragic Case That at Last Got the Police to Pay Attention

Savvy Tokyo's series "Ladies And The Law" digs back in time tracing the catalysts for change in Japanese laws that directly or indirectly affect women and their families. If you have a topic you would like us to cover through a real court case, contact us at editorial@gplusmedia.com

At a little before 1 p.m. on the afternoon of October 26, 1999, Shiori Ino, a 21-year-old university student, was stabbed in the chest while entering JR Okegawa station in Saitama. She bled to death while being rushed to a nearby hospital. Ino’s assailant was a local heavy who had been hired by Kazuhito Komatsu, a 26-year-old man Ino had briefly dated earlier in the year after meeting him at a neighborhood game center.

When they met, Komatsu had given Ino a false name and lied about his age. After just a few dates, he began to simultaneously lavish her with expensive gifts and emotionally abuse her. Ino tried to break up with him, but Komatsu would not accept that she no longer wanted to see him and became even more abusive. He began to phone her home and make threats to both her and her family.

Lack of police involvement

After three months of this, culminating in Komatsu and his friends forcing their way into the Ino home in mid-June with further threats — which Ino recorded — she filed a police report, including the recording she had made. The police told her she had no claim.

When the family endured further threatening phone calls that night, Ino and her parents went together to the police the next day and were again told the police could not, or would not, aid her. Both the police and the free legal clinic they sent her to opined that she was responsible for the problem because she had accepted some of Komatsu’s gifts. No one would help.

Ino tried to break up with him, but Komatsu would not accept that she no longer wanted to see him and became even more abusive.

After Ino sent everything Komatsu had ever given her by courier to his known address, Komatsu and his brother put out the murder contract on Ino that ultimately led to her death. They also continued to make harassing phone calls and other threats to the Ino family and even began to distribute slanderous posters and fliers in her residential neighborhood. Although this continued for several months, still the police refused to act, with the tragic result of Ino’s untimely death.

Even sadder, immediately after Ino’s death, the police reaction was to try to smear the young woman, releasing information that further victimized her by portraying her as a gold-digging slut and implying that she had brought the attack on herself.

Toward the Anti-Stalker Act

It wasn’t until an investigative journalist named Kiyoshi Shimizu reported the true situation that the police finally acted, identifying and arresting the hired murderer, Komatsu’s brother, and the other accomplices in December 1999. (They were subsequently tried and convicted, each now serving time in prison.) Komatsu himself fled to Hokkaido, where he escaped justice by committing suicide in January 2000.

Once the full facts of the case became public, there was a public outcry, leading to an inquiry over the police response, as well as the drafting and passage of an Anti-Stalker Act in November 2000. In that sense, Ino did not die in vain.

[T]he police and the free legal clinic they sent [Ito] to opined that she was responsible for the problem because she had accepted some of Komatsu’s gifts.

Under the Act, two kinds of behavior are prohibited: “pursuit” and “stalking.” Pursuit is any act pressuring another person to go out or in revenge for being rejected, while Stalking is repeated acts that cause the victim to feel endangered.

One hurdle imposed by the Act is that the victim must file an actual criminal complaint in order for the police to act. While this doesn’t sound so difficult, neither is it straightforward. It is a longstanding police practice in Japan (and many other countries) to stay out of domestic or inter-personal disputes, instead urging the parties to resolve the problems themselves or to accept personal responsibility for whatever is happening to them. It is therefore regrettably common for the police to ask victims intimidating questions or making assumed statements such as, “You must have done something to cause this” or “Are you sure you want to file a formal complaint?”

In the Japanese context, this kind of questioning can often result in the victim leaving without taking any official action, choosing instead to endure the situation a little longer, possibly with unfortunate results.

Another potential shortcoming is that the first action the police are authorized to take in “pursuit” cases is a verbal or written warning to the stalker, resorting to a restraining order only if the warning is ignored. Neither of these measures seems likely to adequately protect victims. Indeed, research in Japan has shown that a quarter of stalkers don’t fully recognize that their actions even constitute stalking and instead believe they are justified in their actions.

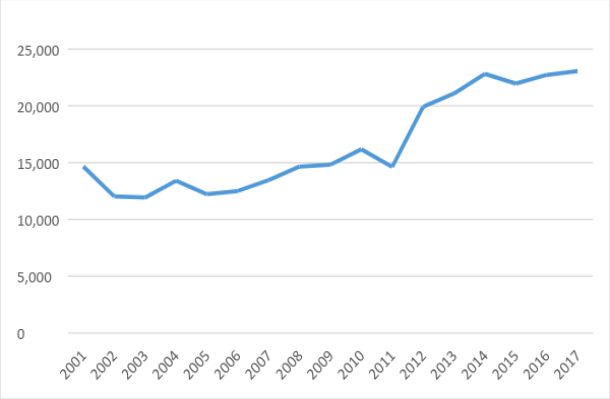

Notwithstanding these difficulties, the number of reported stalking cases has risen pretty steadily in the years since the creation of the law:

Source: National Police Agency website www.npa.go.jp/safetylife/seianki/stalker/H29STDV_taioujoukyou_shousai.pdf

Of course, this is not necessarily because the incidence of stalking is increasing (although that is also possible), but rather, because of greater awareness of the existence of the law, resulting in more of the cases that occur being reported.

Cyber-stalking and cyber-bullying

Since the original 2000 law, the world has changed significantly through the advent of social media. And with it has come cyber-stalking and cyber-bullying — sending multiple unwanted messages to someone via social media, or similarly leaving multiple comments on someone’s blog or social media site. This is particularly a problem for public figures such as entertainment idols, although anyone with an Internet presence could become a victim. Thanks to the ease of electronic communication, immature or maladjusted individuals may grow to believe they have established some kind of relationship with someone they’ve never actually met, and then grow frustrated, hostile or angry when there is no reciprocation.

Research in Japan has shown that fully a quarter of stalkers don’t recognize that their actions even constitute stalking and instead believe they are justified in their actions.

This is what happened to pop singer Mayu Tomita, who was stabbed more than 20 times by a male fan in May 2016. Her attacker had posted more than 300 public messages to her Twitter account professing his love for her and later threatening her life when she did not respond. Fortunately, Tomita survived the attack. But like Ino, she had been to the police after receiving the death threats, and the police declined to act, taking the view that the threats were not serious, possibly because they were made via social media.

After the Tomita incident, the Anti-Stalker Act was revised in January 2017 to include cyberstalking and online harassment such as what Tomita endured. The revisions also increased the criminal penalty for stalking from six months to one year and allow prosecutors to act even without a victim filing an official criminal complaint, at least in circumstances where the victim fears retaliation.

The Anti-Stalker Act was revised in January 2017 to include cyberstalking and online harassment.

As the police are becoming more accustomed to the provisions of the Anti-Stalker Act, and perhaps because they are increasingly coming under criticism when they don’t act to protect victims of stalking, they are becoming more responsive. Still, it appears that only about 10% of complaints filed actually result in official police action.

In nearly 90% of reported stalking cases, the victims are women. The more the society and its institutions provide the means for victims to be brave enough to report stalking rather than suffering in silence, the more people will become aware of what constitutes stalking and why it is inappropriate and unacceptable to society. Calling out and stopping this unacceptable behavior is an obligation we all have, because no one is immune to danger.

Vicki L. Beyer is a Professor of Law at the Hitotsubashi University Graduate School of Law Business Law Department.

Leave a Reply