Been There, Learnt That: Raising Bilingual Teenagers In Japan

Part II: The Teenage Years

In Part I of this column, Louise wrote about the family's efforts to raise their children fully bilingual in their early years. This time, she talks about what the family did in the children's teenage years to reenforce their bilingualism.

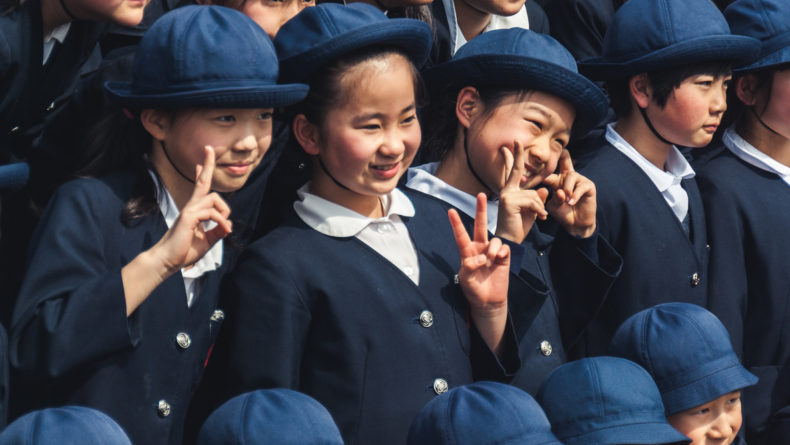

Most kids in the Japanese school system attend public elementary schools, where the educational experience is fairly generic. However, as kids approach their teens and move up to junior high school and then high school, it becomes much harder to generalize.

The choices we made about our kids’ education through the teen years and beyond will not be applicable to every family. Bearing this in mind, I want to present our experiences as just one potential path to bilingualism. Our children are now in university and high school and they are all perfectly comfortable in conversing in both English and Japanese at the same level.

External Influences

Along with Japanese junior high school comes the ubiquitous club activities, or bukatsu. School and friends have more influence over your child’s time and how they spend it, making it challenging for parents trying to fit in a second language at home.

While elementary schools do introduce basic English conversation these days, formal language study with grammar and writing really kicks in from middle school. This is often a time when bicultural children may find that having two cultures and languages draws unwanted attention from classmates and teachers, whether in a negative or positive light. If you add in a healthy dose of hormones and typical teen angst, then you’ve got a recipe for a potentially stressful situation for child and parent alike.

But it isn’t all bad news! There are many wonderful aspects of helping your teen to continue to further develop their language skills. For me, watching my kids bridge from basic “kiddy English” over to using the language with depth and maturity has been an exciting process.

Choosing The Right School

As I noted in Part I of this article, the oldest child is usually both family guinea pig and trailblazer, and that was our son. It had never occurred to me to look at private school for him. In the 6th grade of elementary school, he was an active, sporty kid with a wide range of hobbies and interests—but studying wasn’t one of them! However, that summer I happened to be searching online and found a private junior-senior high school with a solid English program that attracted returnee and bicultural youngsters. The school had recently started a school bus service from the station at the end of our line, making the commute just doable. I took him to an open day that autumn and we both liked what we saw.

By then it was far too late in the game for him to start cramming for the regular entrance exam process. Fortunately for us, kids with a non-Japanese parent had the option to sit an English entrance exam, along with returnee students. He managed to pass the English entrance exam a few months later.

Having two languages has provided me with more opportunities than anything else.

The school followed a typical curriculum in almost all respects, but students were streamed for English. The top two classes in each grade had native speaker teachers and lessons were conducted entirely in English. Our son was placed in the lower of the two, and really enjoyed the holistic and active approach to language learning.

His two little sisters ended up going to the same school from junior high school. Our older daughter had struggled a little bit with her bicultural identity in the later years of elementary school. “I got progressively self-conscious about it, since kids would always pull out the ‘gaijin card’ in an argument. Because I wanted to be ‘normal’, I pretended I couldn’t speak English,” she recalls. However, at junior high school she found plenty of other kids with bicultural backgrounds or experience of living abroad, so having two languages (and a dual cultural background) was no longer a big deal.

Study Abroad

Just as our second child entered junior high, her big brother took off for high school in New Zealand. He had been very happy at his Japanese school but, increasingly, we were seeing that perhaps it wasn’t the best fit for high school and college preparation down the line. College entrance in Japan typically involves a lot of rote memorization and passive studying, which didn’t match his learning style.

We decided to try high school abroad. Fortunately, my parents offered to host my son, which helped us financially and gave me great peace of mind as a mom. Here was another payback for working hard on the English at home—he could communicate well with his grandparents.

My son thrived at his high school. For the first year he was in ESL English, along with other students from overseas, but he moved up to regular English after that. Japanese teens usually just pick one club activity, which becomes all consuming, but my son has always juggled multiple activities. Rather than being unusual, this was the norm at high school in New Zealand, where many kids play more than one sport and balance that with cultural, volunteer or leadership activities to boot.

In due course both our daughters decided to go to New Zealand for high school, too. Studying abroad helped them develop skills in critical thinking and independent study.

Of course there were some surprises along the way. There were “hidden” costs that we hadn’t considered, such as requests for driving lessons (and later, a car!) and ball gowns for school dances. These are not part of the typical high school experience in Japan. Another major cost has been air tickets to get them to and from Japan for vacations. At first I thought that coming back once a year would suffice, but of course it wasn’t enough, and they come home twice a year on average.

Freedom To Choose Their Path

So where are they now? Our oldest is pursuing a Science degree in Australia and starting to think about jobs after graduation. He hopes to eventually utilize his bilingual skills in a global capacity. The little boy who didn’t like to study has grown to appreciate the efforts that went into his English. “Having two languages has provided me with more opportunities than anything else. It’s probably been the most useful skill in terms of opening doors for me. It’s never redundant,” he notes.

Our middle kid has just started medical school in New Zealand. This is definitely a path she could not have pursued in Japan, as her Japanese junior-senior high school did not have a particularly strong science program. Students typically went on to major in humanities, social sciences or education at college. In fact, our daughter didn’t even discover her passion for science until she got to New Zealand. Little sister is still in high school in New Zealand and is active in rowing, choir and lacrosse. We still don’t know where she wants to go for college but it looks like she is leaning towards sciences as well.

While talented Japanese women are making inroads into male-dominated fields, society’s expectations are still bound by traditional ideas about gender. For both daughters, going to New Zealand has opened their eyes to more diverse models of female roles in society.

For other youngsters struggling to fit in a second language around Japanese school, my college-age daughter’s advice is to stick with it.

“When you’re a kid, it’s difficult to realize what a privilege it is to learn two languages, especially because you only start to realize the benefits when you’re a young adult. It becomes your identity and strength. I couldn’t be luckier.”

Practical Information

For a list of Japanese schools in Tokyo that accept students of foreign nationalities, see this article. These schools usually offer an intensive English language program and provide an international environment.

For a study abroad high school experience, see the following organizations:

- World Youth Service Society (WYS) Japan

- Education First (EF)

- Japan Foundation for Intercultural Exchange (JFIE)

- The Experiment in International Living (EIL)

- Youth For Understanding (YFU)

- AFS

“Been There, Learnt That” is a monthly column in which Louise George Kittaka discusses various issues she went through when raising her three children in Japan. If you have any questions for Louise on a topic related to raising bicultural children in or out of Japan, send us an email at editorial@gplusmedia.com or leave us a comment. Louise will answer your questions in her next article.

Leave a Reply