Quill & Tears: Women Writers Who Changed Japan

Part I: From Meiji To Early Showa Era

There’s a face behind every great story.

Though not always receiving the praise and recognition that their work truly deserves, Japan has an endless list of women who changed the country’s history in a number of ways. In our new series focusing on influential women who have made Japan what it is today, we start by introducing 17 of the most influential female writers in Japanese literature.

In this first of two installments, we follow seven women writers from the Meiji period through the Taisho and early Showa eras, an industrious and turbulent time in Japan’s history. It was a time when the emperor’s power was restored and abolished again, the country underwent multiple wars, including WWI and WWII, and European literature along with American cultural and military domination arrived on Japan’s shores. It was an era difficult for all, women maybe even more so.

The 5,000 Faces Of Women: Ichiyo Higuchi (1872-1896)

Ichiyo Higuchi is the pen name for Natsuko Higuchi and if her face looks familiar it’s because it appears on the ¥5,000 banknote. Although Higuchi passed away from tuberculosis when she was just 24, she’s one of the most celebrated Japanese writers and the first modern female to support herself wholly through writing.

Higuchi was born into a poor family, as a result of which she was forced to leave school at the age of 11. Three years later, however, with her father’s encouragement, she began studying classical poetry when she enrolled at Haginoya — one of the finest poetic conservatories in Tokyo. Higuchi felt out of place studying with students from upper class families; a feeling that eventually awoke the writer inside her. She found solace writing a diary which would later turn into a sixty-volume masterpiece, Wakabakage (In the Shade of Spring Leaves).

Higuchi was determined to improve her circumstances and when her good friend Kaho Tanabe was well-paid for a novel, she decided to write short stories based on the shortcomings of the Meiji middle class in order to support her family. Her stories focused on women and their personal torment in situations such as marriage and infidelity. She wrote in a nostalgic pseudo-classical style that combined the living language of the time. Higuchi’s characters and plots became a reflection of the lives and plights of the prostitutes, orphans, and impoverished in the then red-light district.

Her first story Umoregi (In Obscurity) was published in the journal Miyako no Hana and this success prompted her to continue writing stories for literary magazines directed at both men and women. Other popular stories are Takekurabe (Growing Up), Jusan-ya (Thirteenth Night) and Otsugomori (On the Last Day of the Year).

The Modern Girl: Chiyo Uno (1897-1996)

Chiyo Uno embraced modernity in the 1920s and her writing reflects this. She started her career as a teacher but she enjoyed a bohemian lifestyle when she moved from Yamaguchi to Tokyo after winning first prize in a short story competition.

Uno loved the American and European fashion styles and she started Japan’s first Western-style fashion magazine Sutairu (Style) in 1936. She also designed kimonos and organized the first kimono fashion show in the U.S. in 1957.

Uno married and divorced four times, but this unconventional private life gave way to her becoming seen as an important literary figure living as a modan gaaru or moga (modern girl) and writing about the excessive lifestyles and the immorality of the 1920s. Uno was also well-known for having scandalous relationships with other creatives, notably the painter Seiji Toro, and she based her novel Iro-zange (Confessions of Love) on his affairs. The book did very well and she was applauded for writing from a male perspective. Other popular books are the novella Ohan and her bestselling memoir Ikite yuku watakushi (I Will Go on Living).

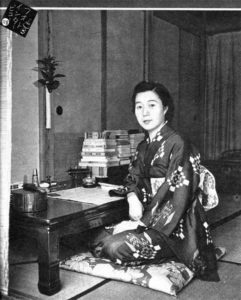

The Late Bloomer: Fumiko Enchi (1905-1986)

Though domestically regarded as one of Japan’s most significant female writers, Fumiko Enchi is relatively unknown in the West. As a child, she was ill for many years, as a result of which private tutors were employed to teach her English, Chinese and French literature since she couldn’t attend regular school. Her grandmother introduced her to Bunraku and Kabuki theater, Edo period classics, The Tale of Genji and Noh dramas, which would greatly influence her work in the future. Enchi enjoyed reading novels by Western authors like Oscar Wilde, but books by Junichiro Tanizaki and their sadomasochistic themes had the most significant effect on her writing.

In her early years, Enchi’s plays were successful, but her novels didn’t have the same appeal. Though she’d produced a number of works already, it wasn’t until the end of WWII that she established herself as a novelist. Enchi won the Noma Literature Prize for her novel Onna Zaka (The Waiting Years, 1949-1957) and the Women’s Literature Prize for Nama Miko Monogatari (A Tale of An Enchantress, 1965). Other famous books include Onna Men (Masks, 1958) and her ten-volume translation of The Tale of Genji into modern-day Japanese.

Her books are psychological in nature: they often deal with ageing women and their sexuality and how women wear masks to hide their emotions. There’s often a story within a story and a shift between reality and the spiritual realm. Her books are also viewed as relevant to the political and social issues prevalent in Japan at the time of writing.

The Survivor: Yoko Ota (1906-1963)

Yoko Ota is regarded as the author of Atomic bomb literature. As a young girl, she read books by Tolstoy, Takuboku Ishikawa and Shusei Tokuda before she became a primary school teacher and a secretary. She married in 1926 and gave birth to a child, but she ran away from her young family and went to Tokyo where she worked as a waitress and a magazine reporter, moving in literary circles and contributing to publications such as Nyonin Geijitsu.

Ota lived in Tokyo, Osaka and Hiroshima for several years and wrote Ryuri no kishi (Drifting Shores) in 1939 and Sakura no kuni (The Cherry Land) in 1940. Ironically, she returned from Tokyo to her native Hiroshima in 1945 to avoid U.S. air attacks. On August 6, 1945, she was at home, about one mile from ground zero, when she witnessed the catastrophic A-bomb that would destroy her hometown. This experience would permeate all of her future writing. Her most famous book on this horrifying subject is Shikabane no machi (City of Corpses, 1948) which was at first censored but later published with several parts deleted. Ningen Ranru (Human Rags) was published in 1951.

Some critics say Ota’s writing is less literary and more structural but it’s definitely an effective depiction of the A-bomb catastrophe and its aftermath in Hiroshima. Ota, herself, admitted it was very difficult to find the right words and writing style to convey the emotions, feelings, and descriptions needed to depict such a tragedy. This writer was forever haunted by the A-bomb and this would affect her writing as well as her mental and physical state right up to her death by heart attack in 1963.

The International Marriage Spotlighter: Tsuneko Nakazato (1909-1987)

Tsuneko Nakazato was the first woman to win the Akutagawa Prize for her short story Noriai basha in 1938. She’s also well-known for writing Mariannu monogatari (Mary Ann’s Story, 1946) and Kusari (Chain, 1959), two of Japan’s most famous novels tackling the subject of international marriage, which she picked after two of her brothers married European women and her daughter, an American man.

Tsuneko Nakazato was the first woman to win the Akutagawa Prize for her short story Noriai basha in 1938. She’s also well-known for writing Mariannu monogatari (Mary Ann’s Story, 1946) and Kusari (Chain, 1959), two of Japan’s most famous novels tackling the subject of international marriage, which she picked after two of her brothers married European women and her daughter, an American man.

Nakazato was awarded the Yomiuri Prize for her novel on the ageing process Utamakura (Song Pillow, 1973), the Japan Art Academy Prize in 1974, the Kawabata Yasunari Prize in 1976, and the Women’s Literature Prize in 1979 for her novel Tagasadeso.

The Foreseer: Sawako Ariyoshi (1931-1984)

This literary legend was well ahead of her time and her books are more relevant now than before her death of a heart attack in 1984. Ariyoshi was born in Wakayama, spent some of her childhood in Dutch Indonesia, studied theater and literature at Tokyo Women’s Christian College, and in 1959 she won a scholarship at Sara Lawrence College in Performing Arts in New York City. She traveled extensively and visited China five times where she once lived in a People’s Commune.

This literary legend was well ahead of her time and her books are more relevant now than before her death of a heart attack in 1984. Ariyoshi was born in Wakayama, spent some of her childhood in Dutch Indonesia, studied theater and literature at Tokyo Women’s Christian College, and in 1959 she won a scholarship at Sara Lawrence College in Performing Arts in New York City. She traveled extensively and visited China five times where she once lived in a People’s Commune.

Her books focus on feminist values, social realism, domesticity, and the role of the artist in society. Her first successful novel Kinokawa (The River Ki) covers three generations of aristocratic women and was made into a popular NHK drama and a film in 1966. Her book Kokotsu no Hito (The Twilight Years) deals with dementia and the ageing population problem in Japan, and the care of the elderly. Fukugo Osen (The Complex Contamination) is about pollution, her travel book Nihon no Shimajima — Ima to Mukashi (Japanese Islands — Now and in the Past) discusses the issues surrounding the Senkaku Islands, and Hishoku (Not Because of Color) tackles racial tension. Her most famous work is Hanaoka Seishu no tsuma (The Doctor’s Wife, 1966), a novel looking into the contrast between the lives of men and women in one family, their social roles and life struggles.

The Queen Of Mystery: Misa Yamamura (1934-1996)

Often compared to Agatha Christie, Misa Yamamura is regarded as the queen of the Japanese mystery novel. Yamamura wrote over 70 mystery novels in her lifetime as well as TV screen plays and theater plays. Her popular series, Catherine Turner, was adapted for TV and video games, and she also acted in several TV dramas based on her own novels.

One thing that not many know about her is that apart from being a master of mystery, Yamamura also held licences for ikenobo, the oldest and largest school of ikebana flower arrangement, as well as tea ceremony, both of which arts she incorporated into her writing.

In Japanese literature, Yamamura stands famous for writing simple suspense stories with a touch of romance, often in popular tourist locations.

In part II of this article we look at influential Japanese female writers from post-war Japan to recent times.