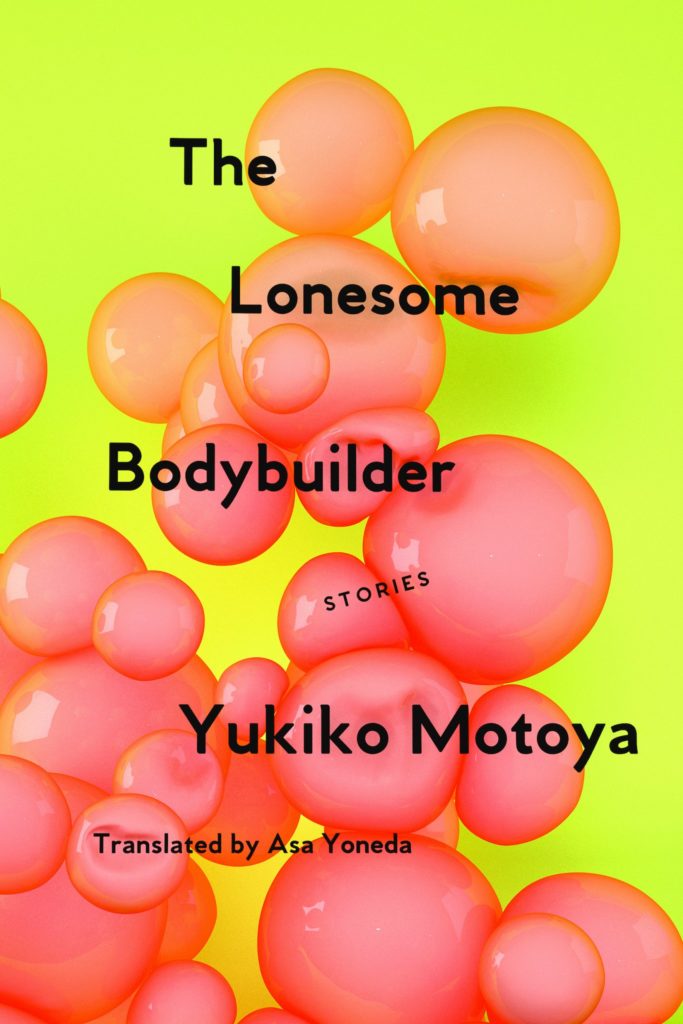

‘The Lonesome Bodybuilder’ Takes Readers On A Dark Journey Of The Woman’s Mind

Book Review: Is This The Black Mirror of Women's Mind?

Brimming with dark humor and featuring a strong feminist stance, we realize that no aspect of modern Japanese life is safe.

Yukiko Motoya is an established name in Japan. Having received the Kenzaburo Oe Prize, the Yukio Mishima Prize, the Akutagawa Prize (among other), she’s now a renowned multi-award winning author, a playwright and a theater director.

The Lonesome Bodybuilder, released in English this November by Soft Skull Press, is the long-awaited translation (by Asa Yoneda) of Motoya’s 2015 collection of eleven surreal short stories which will delight fans of Kafka or Neil Gaiman. If you enjoyed this year’s hit Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata (translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori), then this is an excellent follow-up to her deadpan critique of Japanese society.

Here we have a bizarre set of short stories, brimming with dark humor, that pack a feminist punch and address issues women across borders and generations can certainly relate to. As we read, we come to realize that no aspect of modern Japanese life is safe (for the mind at least) as Motoya skilfully questions what would happen if we take modern behavior to the extreme, holding up a mirror to some of the issues found in patriarchal Japan.

Motoya has been praised for her sensitivity and insight when writing about the psychology and struggles of young women and provides incisive explorations into domestic life. Most of the stories start in a mundane setting: a shop, a family home, the workspace, and become increasingly more surreal and occasionally dark.

Motoya skilfully questions what would happen if we take modern behavior to the extreme, holding up a mirror to some of the issues found in patriarchal Japan.

For example, in the titular “The Lonesome Bodybuilder,” a woman is ignored by her husband and feels she has nothing of her own or interesting in her life.

“Living with my perfectionist husband had made me think I was a person with no redeeming qualities. I’d acquired the habit of dismissing myself.” As a result, she decides to take up bodybuilding and quickly develops an obsession with the sport and her confidence increases tenfold. Her husband, however, doesn’t notice her goliath increase in size until the very end and the societal judgment she faces for her choices begin to isolate her.

Similar in tone, “An Exotic Marriage” features a housewife who is ignored by her husband each evening as he plays mindless games on his iPad, a habit, as it turns out, he has developed due to his need “to switch off.”

“It’s because you’re a housewife San. You can’t understand how men don’t want to have to think about things when we get home,” the gamer husband bluntly says. As she starts growing concerned at his increased lethargy at work, she’s also finding herself getting concerned that his face is melting and moving around to look more like hers.

“Once it was just the two of us, it seemed his attention would slip and the position of his eyes, nose, and things would take on a slightly haphazard placement.’

The longest story in the book and one of the most bizarre is sure to shock you.

In “I Called You by Name,” a woman chairs a meeting at her office but finds it difficult to concentrate due to a growing bulge behind the curtain. As the story progresses we realize the bulge represents her mind and the growing turmoil within it with regards to loneliness, an ex-boyfriend, finding a husband, and having a child: some of the many things she feels she has had to unfairly give up in order to be taken seriously professionally.

[A]n excellent follow-up to [Sayaka Murata’s] deadpan critique of Japanese society.

“When I look at you, I’m confronted by the fact I’ve turned in to a totally uninteresting person. Don’t you dare make me remember who I used to be.”

In one of my favorite stories (simply for how odd it is) “Why I Can No Longer Look at a Picnic Blanket Without Laughing,” (“Fitting Room”), a woman is serving in a clothes shop and is waiting on one of her customers who can’t decide what clothes to buy. Due to Japanese customer service rules (albeit exaggerated) the shop assistant stays overnight and tries to help the customer who won’t come out of the changing room before wheeling her (in the changing room) to another location.

“I was set on find my customer something really special. I thought I’d take her to my favorite boutique. That meant navigating a serious hill through steep residential streets.” As the story goes on, we start to realize that the person within may not be a person at all.

In those eleven of Motoya’s stories, the first thing you notice is that our women protagonists are predominantly unhappy no matter what state they’re in: single, married, working, or not working. Life makes things difficult for women no matter what the situation and the ways they choose to escape the mundane are nothing short of bizarre and hilarious. The Lonesome Bodybuilder is a masterful must-read collection.

The Lonesome Bodybuilder is available on Amazon or directly from Soft Skull Press.

Leave a Reply