“Used, Not Displayed”: Artist Ruri Clarkson On Exploring Feminism Through Fashion

Liberating traditional motifs and breaking barriers Through Embroidery

"I want to liberate traditional motifs from the weight of history and reintroduce them as light as skipping steps of a girl."

Ruri Clarkson is a creative whose work is a little unclassifiable. A self-taught artist, she’s been a painter, an embroiderer and now a clothing designer. Her latest series, her first foray into the world of fashion, Chromatope (deriving from the Greek words for “color” and “a public place”), is currently the best lens through which to explore her ideologies and ambitions as a creator. With Chromatope Clarkson positions herself in two worlds: One foot in the more accessible scene of everyday fashion, the other deeply rooted in the ideologies of the modern-day feminist movement.

View this post on Instagram

Her flirtation with traditional feminine motifs is an exploration of what roles symbolism play in the world of gender identity. They may look beautiful and sweet at first glance, but under the surface, there’s something more subversive.

Following the successful launch of Chromatope at aiiima in Shibuya Hikarie, we met with Clarkson in her home studio in Tokyo. Challenging the stereotypical behaviors that the world expects of women; the politics of the art scene; what living in Hong Kong taught her about motherhood; and what it means to be a feminist in modern day Japan were just some of the many things on her mind.

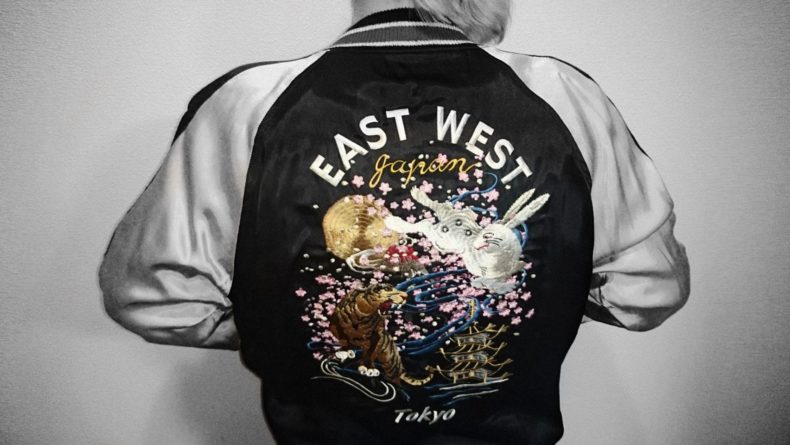

Ruri at her studio in Tokyo, posing with fashion items of her latest collection Chromatope.

Tell us a little more about your most recent Chromatope series. How did it come about? What did you want to say, and how has the response been?

Chromatope is a series that liberates traditional motifs from the weight of history and reintroduces them in a new light.

View this post on Instagram

There were two forces in play in the making of the series. First was the #metoo movement and the women’s march. As a feminist who’s been vocal about some of these issues, it was such an awesome sight to see, and it forced me to think about what I was doing to contribute. At the same time, I was frequenting the permanent collection of the National Museum of Tokyo to feast my eyes on kimono, ukiyoe, and other crafts from the past. I developed a rapport with the silent motifs of kimono and old scrolls, but when I’d go outside under the daylight, I wouldn’t see anyone wearing them.

I felt the motifs sat silent in the darken rooms, similar to so many women who in their own way keep silent in the dark, waiting for the time to speak out. I yanked the retired motifs from the waters of the past, and brought them back into my studio. It wasn’t long before the motifs wiggled into action, and guided me as if having wills of their own. They demanded to be used and not displayed, out and about on the streets, on daily items used by the women of today.

I felt the motifs sat silent in the darken rooms, similar to so many women who in their own way keep silent in the dark, waiting for the time to speak out.

The response has been really great! I’ve done two pop up shops so far, one in Shibuya and one in Fukui now and the collection seems to strike a chord with people regardless of age, gender or where they’re from. Had an experience with an elderly lady who visited the shop, and said about one of my bags; “Oh, this is interesting! This wouldn’t look funny if I had it!”.

Around five years prior to Chromatope you created the series Imposing Words-Contemporary Family Matters. Do you feel like the two series are connected or two separate entities entirely? They touch on similar ideologies but seem rather different in their approach.

They were made to be separate entities intentionally, but they seem to end up next to each other in popup shops/exhibitions to support the one another. Imposing Words started from me scribbling words and images that inflicts discomfort in me, words like “housewife” or “career woman.”

From Ruri’s earlier collection Imposing Words-Contemporary Family Matters. From left to right: “Wife,” “Mother,” “Beautiful (Woman)”

From these notes, I designed a piece, canonizing the word with wordplay inspired motifs. I’d then pick a “feminine” household object also associated with women, to realize the design. The super domestic look of the piece is subverted by bold characters written on it, which causes viewers to do a double take. The “true self” pokes fun at the stereotypical self, mocking its seriousness with less than serious motifs.

Chromtope is directed by my instinct developed by encountering the colors and traditional crafts of the southern U.S., Eastern Europe, Hong Kong, and Tokyo, and the skills I developed in the field of embroidery and fashion through researching and making art. Even though I do want to keep Chromatope free of agenda, for everyone to be able to access it to purely enjoy, I think if people want to know the story, it’s there, and they may feel a personal connection to it.

After you finished college (prior to your artistic career) you started working as a salarywoman. What was the experience like?

It was a tough company, I often found myself working until the early morning. I had a family early on, a year into my new graduate life I had a baby, so I didn’t fit into the cookie cutter “new grad” who was expected to commit her life to the company. It didn’t take long before the long hours started to eat away my health. It gave me a lot to think about in terms of work.

I always grew up thinking my generation could do anything, even if you’re a girl you could grow up to be independent and have a family on top of it. The opportunity for employment was supposed to be equal as of 1985, so what’s stopping us? That’s what I was taught. But my Mom’s generation had a different deal. It was the norm to be a housewife even if you were highly educated.

How did you end up in such a conservative environment? For someone so independently minded, it sounds like a big leap.

I always had this fire in me. When the boys would belittle me saying onna no kuse ni (that’s fresh coming from a girl!) I’d often physically fight them.

I always grew up thinking my generation could do anything, even if you’re a girl you could grow up to be independent and have a family on top of it.

Then I went to college which was a big culture shock. I went to a fully Japanese college, but prior to that, I‘d attended both international and Japanese schools on and off because I moved a lot due to my father’s work. I quickly realized I wasn’t like the typical Japanese girls at college: I wouldn’t clean up after the boys while they smoked, and I didn’t understand the culture of senpai-kohai. I thought to myself, if I’m going to function in Japanese society, I’ve got to learn the demure facade of a Japanese lady, but in retrospect, I think I almost overdid it. By the time I was in my mid-20s, after I’ve had a baby and checked all the boxes of being a “good wife/mother/daughter,” in an outward sense, the pre-teen flame had almost extinguished.

Following the birth of your child, you moved to Hong Kong, which is where you really started producing work. The work that you produced is quite reflective in terms of exploring motherhood and gender. Can you tell us a little about that experience?

The first pieces I created in a vacuum. I made [art] because I felt like I had to for myself. It’s how I solve the issues or the questions I have. When I am done externalize it in a form that I can touch, and then I can move on.

When I was in Hong Kong and started making artwork, I thought that feminism would help me solve the issues I had, although I had some hesitation at the beginning because I thought it’s too strong of a position. Silly me! So, I would travel back to Japan and go to the big library in Hiroo and I would sit there for three days and read a bunch of sociology and women’s studies books. It was eye-opening because I didn’t study any these things at school. At the time I was still creating pieces just for myself.

[Making art is] how I solve the issues or the questions I have.

How did living outside Japan change your perspective on society?

One of the biggest surprises for me was that if you’re middle class or upper class in Hong Kong, it’s very easy to afford a domestic helper. The women are typically Filipino and Indonesian and there’s so many of them that this culture was very public. Because these women don’t have a lot of money, when they have a day off they would all go to Victoria Park and hang out.

These women would fulfill all typical family and children duties; things I’d been taught were “labor of love” of the mother. In Hong Kong it’s very different, the moms would be at work and the helpers would take care of the children.

Neither way is right or wrong, but for me, the image of what a mother was meant to be was totally shattered. The women weren’t paid a lot, so the whole idea of putting a monetary value on parenting was a concept that had never even crossed my mind. It was a lot to reflect on.

Do you consider yourself part of the art world or the retail world now?

I communicate through visual creation and I just have so many ideas for both. One does not have to fit into people’s lives on a daily bases, and the other does, so the challenge of bringing it to life is different but the intention is the same. It is my way of communicating my ideas, hoping it gives joy and hints that people can use. One thing I am intentional about is communicating to people who were once girls. I call them “post-girlies.” My move to fashion was largely because my target audience is there.

The atmosphere of the contemporary art world is quite macho.

I would sometimes get comments and suggestions on my work like “men like it more like this, or that.” Or, “if you’re going to be a feminist type artist you should be crazier.” The atmosphere of the contemporary art world is quite macho. It’s a common knowledge amongst women artists that you have to watch out for these mansplainers who have a huge ego. I know artists who were sexually or morally harassed by gallery owners or male customers. But it’s lawless because it’s not like you’re employed by them.

Who do you make work for?

When I make fashion items, I think of my friends and what would bring a smile to their faces and make them feel confident. I also want to do justice to the beautiful traditional motifs that I am depicting in my style in the Chromatope series. I’ve been a feminist and an artist for a few years now, and last year’s women’s march was a big turning point. The term Feminist used to be sneered upon, but now it’s for everyone. I felt that I can release little nuggets of it even in retail, because it’s more consumable as an idea now, thanks to the generations of women who came before us.

Your previous work had an undercurrent of social commentary, how do you separate your politics from these more everyday pieces?

I made Chromatope so it’s separate from the person. I think fashion designers have the freedom to express their vision of beauty more removed from themselves. Chromatope is like a garden I tend for myself and others to have a stroll in or enjoy. At the same time, however much I separate them, I’m making them so there’s always going to be a feminist undercurrent. But style choices are arbitrary, right? For example, Chromatope’s style element is classical, feminine and with playful colors and motifs — not everyone who has a connection to my artwork is going to want to wear it and vice versa.

What are your plans for the rest of 2018?

Following my recent exhibit, I’m currently exhibiting/taking semi-custom orders in a select shop. I saw first hand how people’s face brightened up with the idea of creating their very own clothing. So I am experimenting with taking semi-custom orders, consulting with customers about motif choices on their blouse top. Another way to make your own clothes is to actually embroider it yourself. I got a lot of requests for workshops, and I recently found a place that looked really good. I think that’s probably going to happen in November. I also have many inquiries from individual customers abroad, so I am considering ways to bring Chromatope to other cities around the world.

To learn more about Ruri’s work, visit her official website.

Leave a Reply