‘Only Women Know How To Vacuum’ And Other Stories Of Workplace Sexism In Japan

Two Women Share Gender Inequality Workplace Experiences In Japan

Some rules are made just for girls, they say. Here’s to breaking them all.

After having experienced my own fair share of less than cool comments and some rather interesting conversations while working in Japan, I decided to reach out to other women working here to hear about their experiences. In this article, I share a story of my own and two real-life anecdotes from a Korean friend who has been working here all her life.

Only women know how to vacuum

My Japanese boss is wrestling with the many plants in our office. I see him muttering to himself as he goes from plant to plant, tending to some of their dead leaves and varied dehydrated states. I can’t hear what he’s saying because I have headphones on. I’m editing a trailer that’s due at the end of the day when I hear a muffled sound that can’t be from the video. I hear it again, it’s louder the second time.

Having both heard the muffled command, my coworker and I take off our headphones at the same time. Our boss gestures for us to come to his side of the room, so we follow, leaving behind our time sensitive projects. We join him next to a particularly forlorn plant and he explains that customers are coming soon. He says that we need to make the office look clean and presentable. Both of us nod to show that we care and understand. He gives my coworker, John, a strange look that neither of us understand at the time. There’s a small vacuum in our boss’s hands. He lifts it off the floor, points to the carpet, and says in English, “Clean please.” We both nod again. John reaches for the vacuum.

Sit, sit, John. Please sit. You can continue editing. You are a man.

Our boss’s eyes widen. He seems even more confused than usual, leans back clutching the vacuum to his chest, just out of John’s reach. There’s a few awkward moments where the three of us don’t know what to do or say when finally our boss lets out a huge laugh. He bends over, clutching his knees for support. John and I exchange perplexed glances. Our boss straightens up and hands me the vacuum while speaking to John.

“Sit, sit, John. Please sit. You can continue editing. You are a man.” He says in Japanese, still laughing. He points to me and says my name to John, “It’s her job to vacuum, don’t you think?” John looks at me with eyes that say, “Oh my god, I’m so sorry.” He returns to his seat, and I’m left standing next to that particularly dry plant in a state somewhere between shock and rage.

The boss walks away laughing, shaking his head and repeating John’s name as if he was the funniest jokester on the planet.

Unwilling to inhabit a world where plants were deprived of water and women were dispensable cleaning devices, I left that job. That’s when I resolved to ask other women in Tokyo to see if they too had experienced similar transgressions made at work, the first being a close friend, Hana Lee, (pseudonym), a 29-year-old Korean woman who grew up in Japan. I made plans to meet with her for coffee and some breakfast and hear about her stories of what it has been like for her to work as a woman in this country, specifically in the field of media. Here are some of her stories, recounted anonymously, retold accordingly in a first-person perspective.

Only men can have opinions

© Photo by Jes Kalled

© Photo by Jes Kalled

A few years ago I was working at a trading company in Tokyo and had a boss, a Korean man in his 50s, with a terrible sense of humor. He would often make degrading jokes about women, but of course they were just “jokes,” so as employees we could never really object to them. One day, my boss asked me to meet to talk about our projects.

I don’t even remember what it was that I disagreed with him about during the meeting, but it had to do with our projects at that time.

You speak your opinion quite directly. I don’t think you’ll be able to get married.

He looked at me and said, “You speak your opinion quite directly. I don’t think you’ll be able to get married.” I said, “No, I think I will be able to.” I knew he felt he could say that because I was the youngest woman in the office. It was a reflection of the deeply rooted workplace hierarchy scene in Japan, and I was at the bottom by default.

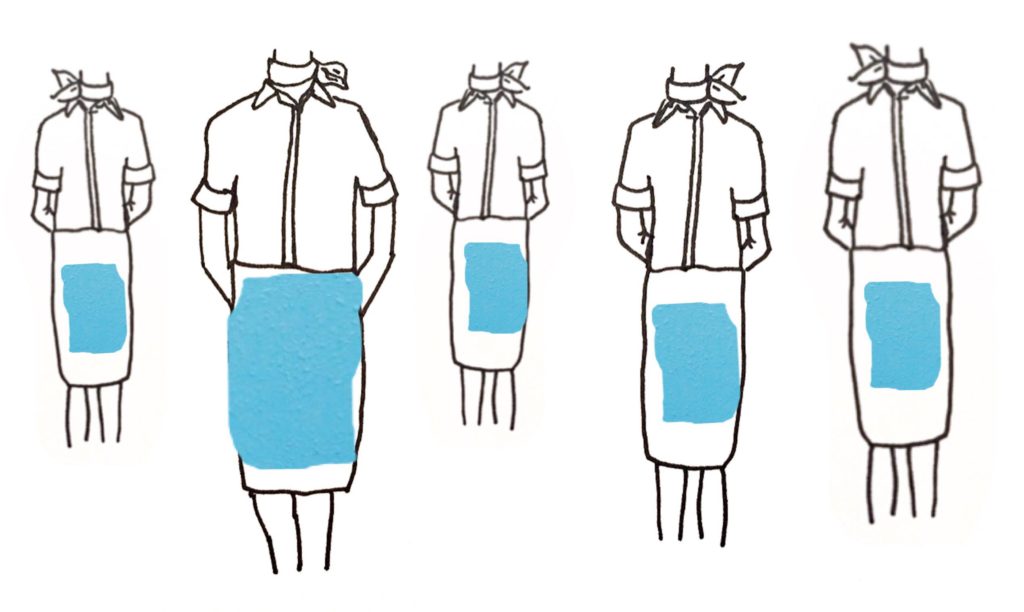

One of the things I hated most about that job was the uniforms. Only women were required to wear them. It somehow identified us only as “girls” or “women” washing out any chance of our personalities or creativity shining through. We all looked the same. After awhile, I quit. And so did a bunch of other women after me.

© Photo by Jes Kalled

© Photo by Jes Kalled

Only women without makeup can be assistant directors

It was my first video shoot with my new job title at a Japanese TV production company. The producer I worked for, a Japanese man in his 60s, brought me over to meet the director, who was an outside hire, a freelancer. They shook hands like old friends and I was introduced as the new assistant director for the production company. I was young and somewhat inexperienced, but I knew my worth. However, the director had other ideas. He took one look at me, and then looked back to my boss.

“Really?” he asked.

My boss nodded and said, “Really.”

“Where did you find her?” The director asked.

“We interviewed her.” My boss replied.

“Yes, I just sent in my CV and applied to work with this production company.” I said, slightly confused at why this wasn’t obvious.

The director looked to my boss again and replied, “Oh, I thought perhaps you just picked her up off the street.”

After the producer left, the director approached me again, asking, “Seriously though, how did you get this job?” I told him I sent in a CV, and went to an interview.

“Really?” He asked again.

I could tell that he didn’t take me seriously at all. I also think he was implying that I had gotten the job by means other than an innocent CV. Plus, of the female assistant directors that are in the industry, it seems they don’t usually wear makeup like I do. My style stood out, which apparently made me a target for doubt and criticism. If I were a man, my position wouldn’t be in question. And here I was simply wearing clothes and makeup of my choosing; my appearance harnessing enough power to cast shadows of disbelief about my abilities on the first day. I wanted to tell him: I don’t dress up to attract men, I dress up because I love dressing up. And what does that have to do with anything anyway?

I wanted to tell him: I don’t dress up to attract men, I dress up because I love dressing up.

Hana’s stories didn’t stop there. There were many more. When our conversation came to a close, I capped my pen and closed my notebook. But the air was still filled with her floating words, leftover thoughts, and a kind of residual anger that only an unresolved situation can give life to.

“What can we do about all this?,” we asked each other.

“Well, we just did something.” I said, nodding towards my notebook on the table, pen wedged inside.

In Part II of this article, we will be featuring other women and men’s stories on gender inequality at the workplace in Japan. If you have a story to share, contact us at editorial@gplusmedia.com (anonymity guaranteed) or leave a comment here if you don’t mind sharing your story publicly.

Leave a Reply