11 Facts About The Ukiyo-e Master Kitagawa Utamaro

Who Is This Mysterious Bijinga Master?

Nearly two centuries after Kitagawa Utamaro's artworks were first introduced to the world, the mysterious man behind Japan's most famous bijinga (ukiyo-e portraits of beauties), never really went out of fame—but what do we really know about this mysterious artist?

He is known for producing some of the world’s best-known ukiyo-e prints, he is considered as “a master of femininity” and an “expert on women.” He is presumed to have created thousands of designs and artworks and has served as an inspiration for even more. And yet, to the global art world, the life of Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806) is still veiled in uncertainty.

Moon at Shinagawa; Kitagawa Utamaro (1753–1806); Japan, Edo period, ca. 1788; painting mounted on panel; color on paper; Freer Gallery of Art, Gift of Charles Lang Freer

1. There are no records on who he was

Utamaro Kitagawa (1753-1806) is presumed to have produced some 2,000 works in his lifetime and is credited for some of Japan’s best-known ukiyo-e of all times, but there are no existing records—no letters, no diaries, nor work-related documents—that shed light on who he was, how he lived, or even how he looked.

The little we know of him is to a large extent uncertain: Utamaro was probably born in 1753, possibly in Edo—now Tokyo—, may have been married and may have had a child; may have lived in one of Edo’s pleasure quarters, or may have had a father who did. While there are numerous speculations and theories about his life, very few are supported by historical evidence.

2. He was a freelancer-turned-pro

If Utamaro was living in modern times, we would most likely know him as a freelancer—a very well paid one, in fact. As part of their marketing efforts, commercial publications in the 18th century Edo would hire on-the-project artists to produce images of “approved subjects”—kabuki, sumo, courtesans, beauties, famous places, and anything else that wouldn’t depict political or controversial images.

It is believed that Utamaro became one of those “brush for hire” artists around the 1780s when he was spotted by a famous publisher at the time. His portraits would quickly become popular, establishing him among the most sought-after ukiyo-e artists and a specialist in the genre of “beauties.”

Takashima Ohisa Using Two Mirrors to Observe Her Coiffure Night of the Asakusa Marketing Festival, ca. 1795, woodcut, MFA Boston

3. He painted mostly women, but no one knows why

While we know for sure that he enjoyed depicting women—for the mere fact that most of his paintings portray pretty ladies—, it is not entirely clear why he focused on that genre. It is most likely that he was initially hired for a related project, turned out to be so good, people starting talking, and he officially became “the expert on women” we know him as today.

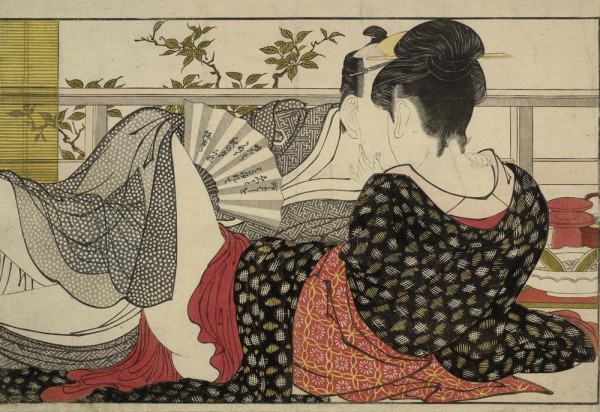

4. He may have been a regular customer at Edo’s licensed brothels

Utamaro painted not only beauties playing musical instruments and wearing stunning kimono, but he is also well known for producing hardcore Edo erotica, known as shunga. His detailed depictions of the life—and sex—taking place in the then Tokyo’s licensed brothels indicates that he was a well-informed insider. Was he there for professional inspiration or for other reasons? We’ll most probably never know.

Lovers in the upstairs room of a teahouse, from Utamakura (Poem of the Pillow), ca. 1788, sheet from a color-woodblock printed album, The British Museum, London

5. His Snow, Moon and Flower is a mysterious triptych

Three of Utamaro’s most famous paintings, Moon at Shinagawa, ca. 1788, Cherry Blossoms at Yoshiwara, ca. 1793, and Snow at Fukagawa, ca. 1802-1806, are believed to be completing a triptych, known as Snow, Moon and Flower.

The trio is considered one of Utamaro’s masterpieces and it portrays courtesans at three of the then most famous brothels: Shinagawa, Yoshiwara and Fukagawa in three different seasons. It is believed that the trio was created for a wealthy patron based in Tochigi prefecture and it sparkled interest in Kitagawa Utamaro’s work in 19th century Europe, when it was brought to Paris for an expo. It is also exactly those three paintings that would later become the most perplex mystery related to his work.

Cherry Blossoms at Yoshiwara, ca. 1793, Hanging Scroll, Wadsorth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CA, USA

6. Snow, Moon and Flower lasted together only temporarily

Last seen together in 1879, the three paintings are believed to have been brought to France and presented at the Paris World Expo the previous year. But the trio didn’t last long together: Charles Lang Freer, the founder of the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., acquired Moon at Shinagawa in 1903; Cherry Blossoms at Yoshiwara passed through several hands before entering the collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art also in the U.S. in the late 1950s, and Snow at Fukagawa returned to Japan in the post WWII period as part of a buyer’s private collection.

7. His painting Snow In Fukagawa went missing for 70 years

After the painting was brought back to Japan in the late 1940s, it was displayed at the Matsuzaka department store for several days. The painting then went missing until the Okada Museum of Art in Hakone, announced that it was discovered and reclaimed it in March 2014. How it was discovered and in whose possession it was for all these years remains a well-kept secret.

8. Snow, Moon, Flower breaks all triptych standards

Triptych is in most cases a picture on three panels, typically hinged together vertically and used as an altarpiece or a set of three associated works intended to be appreciated together. Apart from the fact that the three paintings depict courtesans at three brothels, nothing else unites them. The paintings are of different sizes and paper—Moon and Snow are depicted on two large sheets of paper, while Cherry Blossoms is painted on eight smaller sheets. According to scholars, this indicates that the trio was completed at different times, and that pretty much breaks all triptych standards.

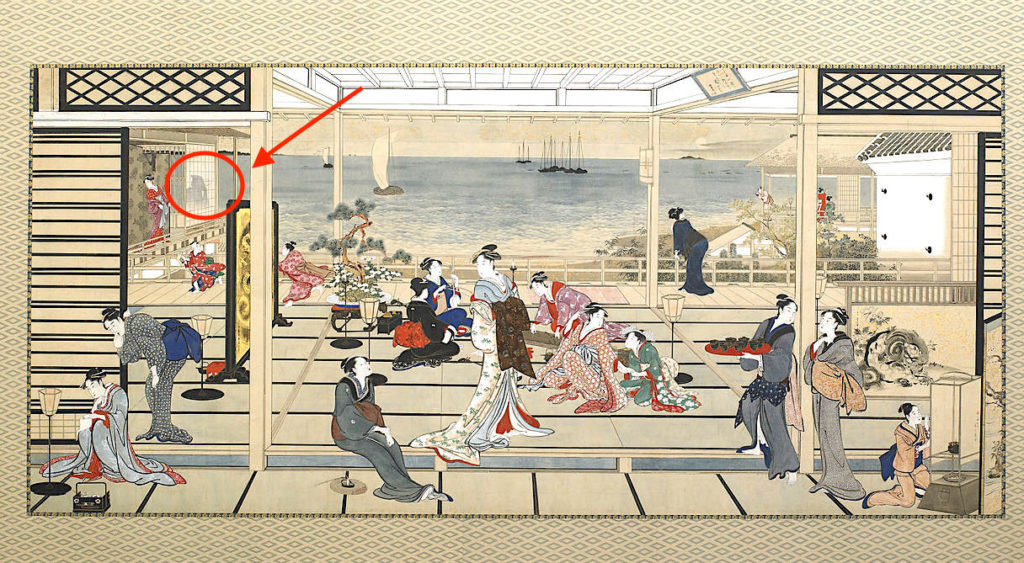

9. He may have painted himself in Moon in Shinagawa

So Utamaro enjoyed painting women, but once in a while he also took the pleasure of having men in his works and art scholars believe he may have secretly done this in Moon In Shinagawa! On the left side of the painting we can see a woman in red kimono and a silhouette next to her. She is hidden behind a Japanese paper screen, smoking—or holding a paintbrush. Some Japanese scholars believe this may be a secret self-portrait…

Could this be a hidden self-portrait of Kitagawa Utamaro?

10. He was involved in Edo period’s most infamous censorship arrest

In 1804, Utamaro was sentenced to three days in prison and 50 days of home arrest in handcuffs over paintings in which he depicted the famous military ruler Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The paintings are believed to have been Utamaro’s opposition against political reforms to censor popular culture, including ukiyo-e, that was just starting to take place at the time.

Artists were not allowed to portray famous political figures, yet Utamaro, openly painted Hideyoshi in various lustful poses, clearly mocking his lavish lifestyle and sexuality. Utamaro, a rebel of his time, even went ahead and signed the paintings, which brought him to jail and caused his health to deteriorate until he eventually died two years later.

Hideyoshi and his Five Wives Viewing the Cherry-blossoms at Higashiyama, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The painting is one of the series of prints that got the artist in trouble for mocking the political figure.

11. His original triptych can be seen in only one place in the world

The triptych is currently divided between two continents: Moon at Shinagawa is preserved at the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., Cherry Blossoms at Yoshiwara remains a possession of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, also in the U.S., while the newly rediscovered Snow at Fukagawa is kept at the Okada Museum of Art.

Based on the will of Charles Lang Freer, the founder of the Freer Gallery of Art, no paintings are allowed to leave the gallery, even for temporary exposure. That is why, the original Moon at Shinagawa can only be seen at the Freer Gallery, and with it the triptych can only be reunited there, in the U.S. The last time it happened was in 2017 at the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery , and we are now waiting for a new opportunity to admire this triptych as a whole again.

This article was originally published in 2017 and edited on May 27, 2020.