9 Japanese Female Authors You Should Add To Your Reading List

Meet the modern queens of Japanese literature

Contemporary Japanese literature is so much more than its internationally famous son of the soil, Haruki Murakami.

Talk to the average Western bookworm and they’ve probably heard of Japan’s most famous literary export, Haruki Murakami. Murakami is great — don’t get me wrong — but reading predominantly his works is merely scratching the surface of modern Japanese literature. Many talented women writers in Japan also offer a different perspective on Japan, particularly regarding gender norms and roles. Here are nine of our very favorite female writers to help you diversify your J-lit reading experience.

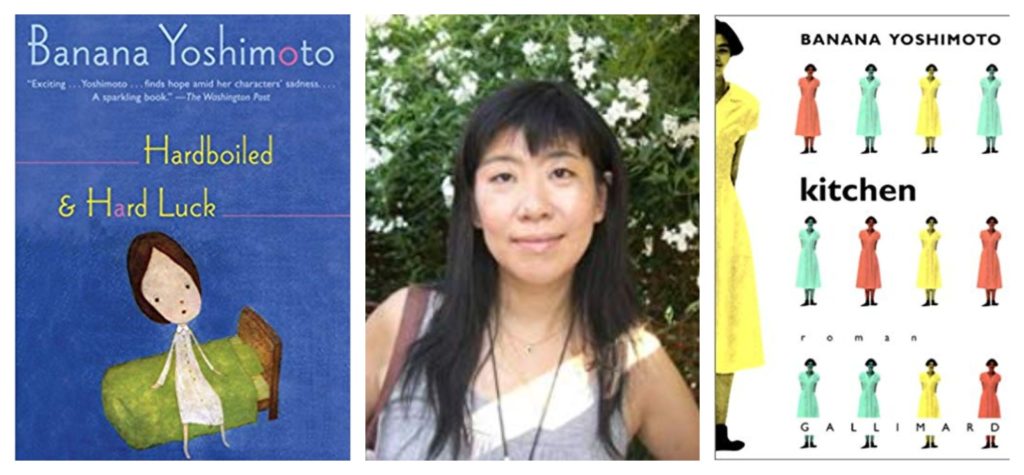

1. Banana Yoshimoto (吉本 ばなな)

Born in Tokyo in 1964, Yoshimoto has been serving up delicious fiction since the late 1980s. Yoshimoto grew up in a very liberal Japanese family with a famous intellectual father and popular manga artist sister. She started writing at the age of five and has continued writing stories because she finds it enjoyable. Yoshimoto changed her first name from Mahoko to Banana because she adores banana flowers and considers her pen name “cute” and “androgynous.” In fact, she loves the fruit so much she has a tattoo of a banana etched on her right thigh.

Her English-language debut and best-loved work to date is Kitchen (1993, translated by Megan Backus), a book she wrote during her downtime as a waitress at a country club in Tokyo. The novel is split into two stories that feature female protagonists trying to cope with death and loss. She also has a collection of surreal short stories called Lizard (2001, translated by Ann Sherif) that uses magic realism to examine the lives of ordinary people in Japan.

Why read Yoshimoto: Yoshimoto’s writing style is very breezy and surreal, making her work a pleasure to read whether you’re on the train or in the bathtub. Although she explains that death is a common motif in her work, her love of cooking also resonates in her writing so that her books will appeal to foodies as well. You can follow her on Instagram, which she says she doesn’t update regularly or learn more about her through her official website.

Recommended reads: Kitchen, Lizard

2. Yoko Tawada (多和田葉子)

Although born in Tokyo in 1960, Tawada moved to Hamburg when she was twenty-two and still calls Germany home today. It seemed like destiny that the daughter of a Japanese bookseller and translator would eventually become a writer of translated fiction herself. She went on to earn a Ph.D. in German literature and to write a series of mind-bending novels in German and Japanese.

Since then, she has won several literary accolades including the Akutagawa Prize in 1992 for Inu Muko Iri (The Bridegroom was a Dog) and the Goethe Medal in 2005 and Kleist Prize in 2016. She also became a global literary star when her novel The Last Children of Tokyo (2018, also published as The Emissary, translated by Margaret Mitsutani) won the US National Book Award for Translated Literature in 2018.

Why read Tawada: Tawada’s work will appeal to anyone interested in Kafkaesque literature with lots of delightful wordplay. Her work explores a lot of “what if” questions: what if circus polar bears could talk or what if the old could outlive the young in post-apocalyptic Japan?

Tawada is also able to use magical realism to satirize real-life events and consequences to make her readers think more deeply about the world around them. For example, Memoirs of a Polar Bear was inspired by a real-life polar bear, Knut, born in captivity at the Berlin Zoo.

Recommended reads: The Last Children of Tokyo, Memoirs of a Polar Bear (translated by Susan Bernofsky)

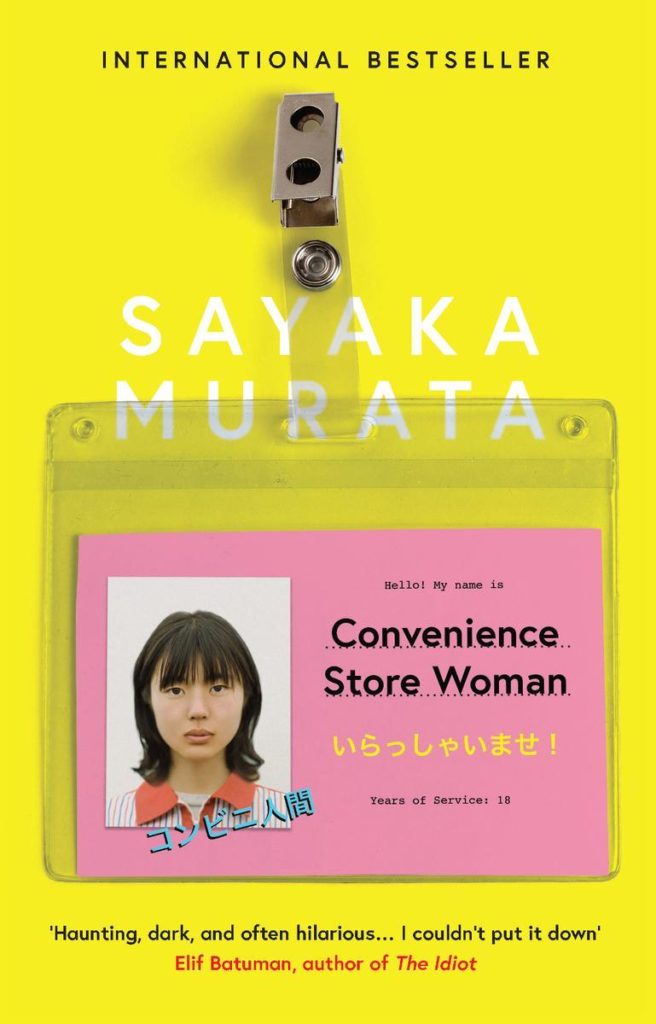

3. Sayaka Murata (村田沙耶香)

Sayaka Murata is no stranger to critical acclaim. She has won several literary prizes in Japan including the Gunzo Prize for New Writers in 2003 for Junyu (Suckling) and the Akutagawa Prize in 2016 for Konbini Ningen (Convenience Store Woman). She has recently been on the hotlist in Western bookstores because of her runaway hit English language debut, Convenience Store Woman (2018), translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori.

Murata, like many of her novels’ protagonists, is a bit of an oddball herself, still living at home with her homemaker mom and judge dad. She was inspired to write her hit novel based on her own experiences working in convenience stores in Tokyo for almost eighteen years. In fact, she found that working shifts at the stores helped to structure her writing life. However, since 2017, she has quit the konbini life and has been writing full-time.

Why read Murata: Murata’s darkly comic and minimalist prose will appeal to any reader who likes reading about the outsiders in society, the ones who don’t quite fit in because of how they think about everyday things like sex, marriage, and work. For instance, in Convenience Store Woman, Keiko even dresses like her boss in order to avoid social shaming.

Recommended reads: Convenience Store Woman, A Clean Marriage (translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori)

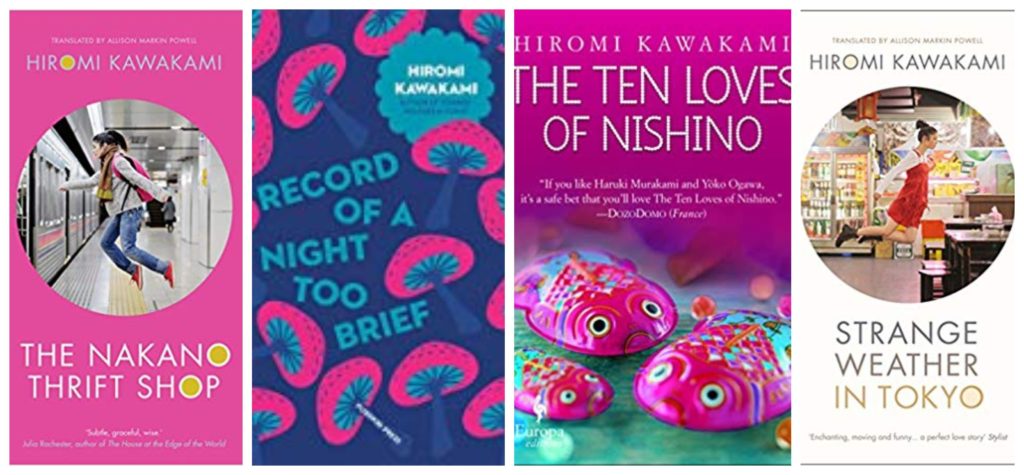

4. Hiromi Kawakami (川上 弘美)

Kawakami’s fiction has been described as “quirky,” “offbeat,” and “sweet” and her writing style has often been compared to Banana Yoshimoto’s. However, that doesn’t diminish the individual charm of her work. Born in Tokyo in 1958, Kawakami is a writer dedicated to her craft. She professes that although she writes in the morning and afternoon, she thinks about writing all day.

After stints as a science teacher in middle and high school, she published her debut novel, Kamisama (God) when she was 36. It won the Pascal Short Story Prize for New Writers. She then won the Akutagawa Prize in 1996 for Hebi o Fumu (Tread on a Snake) which was translated into English as Record of a Night Too Brief. She cites Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude as a major influence on her fiction writing.

Why read Kawakami: Like Murata, Kawakami’s fiction offers delightful slice-of-life scenes in coffee shops, bars, forests, and houses but also explores larger themes of alienation and loneliness in the big city of Tokyo. For instance, in Kawakami’s Strange Weather in Tokyo (translated by Allison Markin Powell), we meet Tsukiko who reunites with Sensei, her former high school Japanese teacher, and ends up pursuing a strange yet close relationship with this man from her past.

Recommended reads: Strange Weather in Tokyo, The Nakano Thrift Shop (translated by Allison Markin Powell)

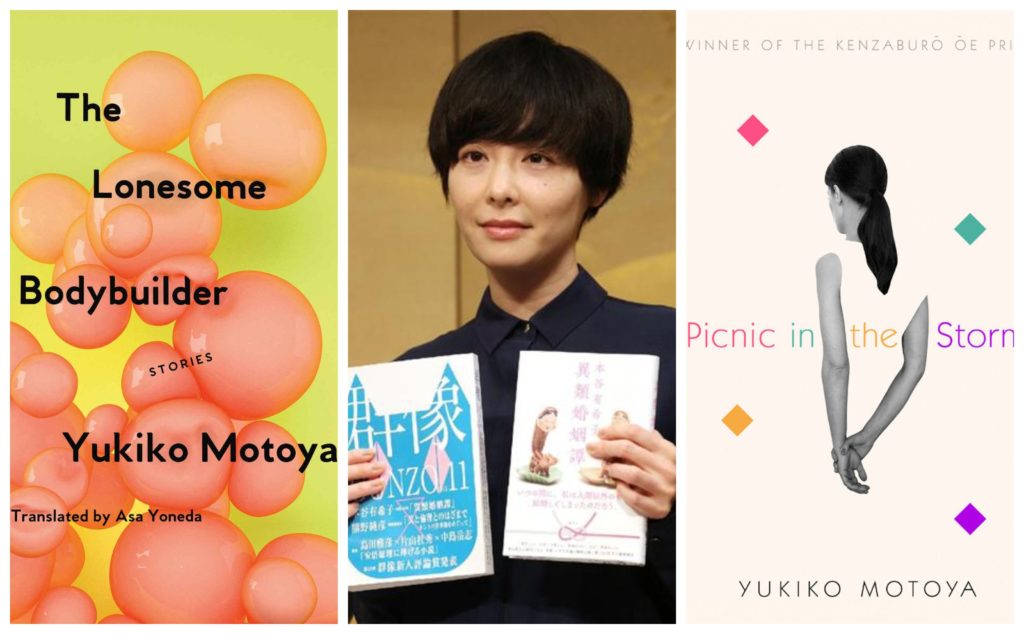

5. Yukiko Motoya (本谷有希子)

Born in Ishikawa Prefecture in 1979, Yukiko Motoya is another female Japanese writer who delivers eleven eye-poppingly strange short stories in her collection, The Lonesome Bodybuilder (2018, also published as Picnic in the Storm, translated by Asa Yoneda). She also won the coveted Akutagawa Prize in 2015 for Irui Konin Tan (Tales of a Marriage of a Different Sort).

Motoya’s career is certainly diverse, taking the scenic route via voice acting, radio DJing, playwriting, and stage directing. She first dove into fiction in 2002 with the publication of Eriko to Zettai (Eriko and Absolutely). Unlike many other taciturn Japanese novelists, she has been described by Nobuko Tanaka of the Japan Times as “a darling of the Japanese media” due to her frequent media appearances.

Why read Motoya: Motoya’s stories in The Lonesome Bodybuilder reveal the inner workings of the individual and the skewed relationships of ordinary people. Her style is both bleakly humorous and surreal, blurring the boundaries between fantasy and reality. For instance, in “Fitting Room” a store clerk waits on a customer for days although she isn’t sure if the customer is human or not.

Recommended reads: The Lonesome Bodybuilder

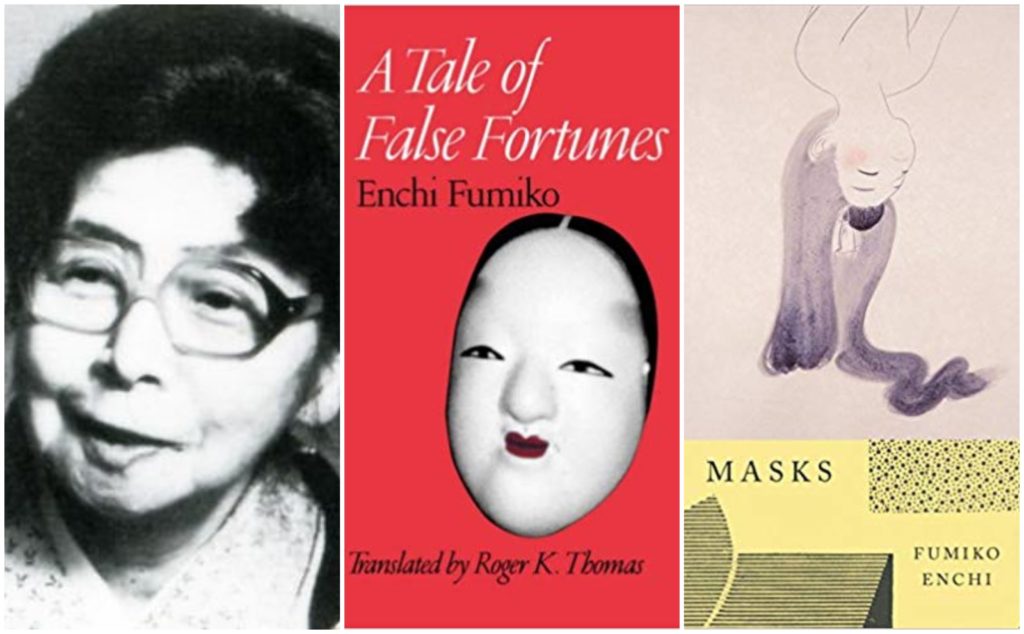

6. Fumiko Enchi (円地 文子)

If you’re new to Japanese lit by female authors, Order of Culture recipient Fumiko Enchi is one writer you should not overlook. Fumiko Ueda, as she was then known, was born in Tokyo in 1905. Because she was a sickly child, she was often home-schooled and exposed to classic and modern Japanese literature as well as modern Western writers like Edgar Allen Poe and Oscar Wilde.

As an adult, she wrote plays but turned to novel writing when her daughter was born. Her life was tragic. During World War II, her home and possessions were destroyed and her health continued to deteriorate over the years. Likewise, her fiction reflected physically and emotionally disturbed women. She eventually became known as one of Japan’s most notable feminist writers.

Why read Enchi: Enchi is skilled at blending traditional Japanese culture in a contemporary setting. Also, if you’re keen on deep psychological portrayals of women in post-war Japan, check out the English translation of Onnamen, Masks (1983, translated by Juliet Winters Carpenter). The story delves into the relationship between a scheming mother-in-law and her widowed daughter-in-law and how she manipulates those around her to get what she wants. Masks is also a great introduction to Japanese shamanism, the Tale of Genji, and the Noh tradition of masks.

Recommended reads: Masks, The Waiting Years (translated by John Bester)

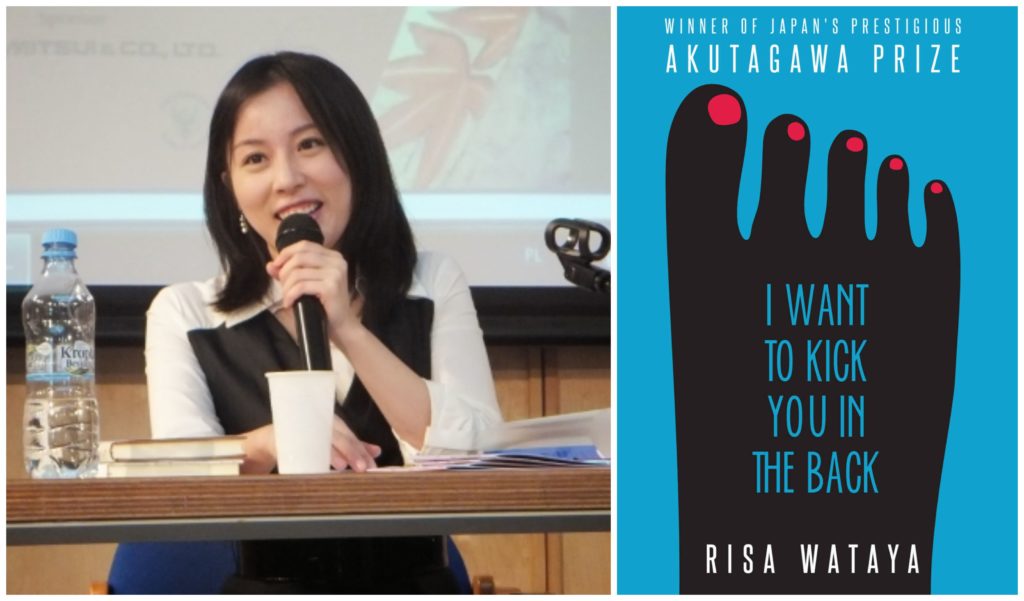

7. Risa Wataya (綿矢 りさ)

Born in 1984, Wataya wrote her first novel Insutoru (Install) when she was still in high school. It won the Bungei Prize in 2001. She then wowed literary critics when she won the prestigious Akutagawa Prize (jointly with Hitomi Kanehara) in 2003 for Keritai Senaka (I Want to Kick You in the Back, translated by Julianne Neville). At the time, she was still a nineteen-year-old student at Waseda University, which made her the youngest winner in the history of the coveted title.

After she won the Akutagawa prize, she experienced a writing slump and dove into a series of part-time jobs including working at a hotel and at a clothing store. She credits these experiences as giving her the inspiration to write again. Her work then evolved from featuring high-school protagonists to adults such as the daydreaming clerk in Kawaisou da ne? (Isn’t She Pitiful?) which won the Kenzaburo Oe Prize in 2012.

Why read Wataya: Wataya’s early work captures the zeitgeist of coming of age in post-bubble era Japan and is likely to appeal to teenagers and young adults struggling with the awkwardness of fitting in and developing relationships with the opposite sex. I Want to Kick You in the Back focuses on a girl in high school who struggles to relate to those around her and develops a love-hate relationship with another loner in class.

Recommended reads: I Want to Kick You in the Back

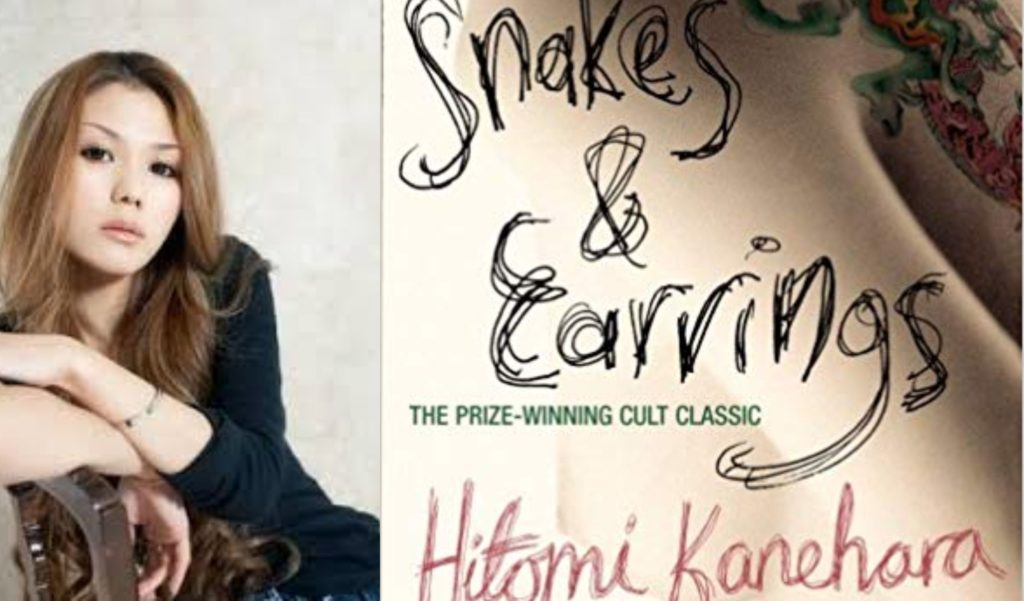

8. Hitomi Kanehara (金原 ひとみ)

Born in 1983, Kanehara became the poster child for rebellious young people in Japan in the early 2000s. Although she was the daughter of a university professor and children’s books translator, she dropped out of high school and left home at a young age, choosing to live on the streets of Tokyo. Kanehara confesses that much of her early fiction was inspired by her own rough-and-tumble life, including her depression and self-harm. In spite of this, her father continued to support her and helped her hone her writing skills.

At age 20, Kanehara shocked a lot of people when she won the Akutagawa Prize (together with Risa Wataya) in 2003 for her debut novel, Hebi Ni Piasu (Snakes and Earrings, translated by David James Karashima). After the Fukushima disaster in 2011, Kanehara moved to France with her husband and two children where she continued writing.

Why read Kanehara: Kanehara’s Hebi Ni Piasu is likely to appeal to millennials because it focuses on the life of a gyaru (street girl) in post-bubble Japan with graphic references to sex, sadomasochism, body modification, eating disorders, and self-harm. Her later work, however, deals with themes like motherhood and marriage, mirroring the author’s own maturity and age.

Recommended reads: Snakes and Earrings, Autofiction (translated by David James Karashima)

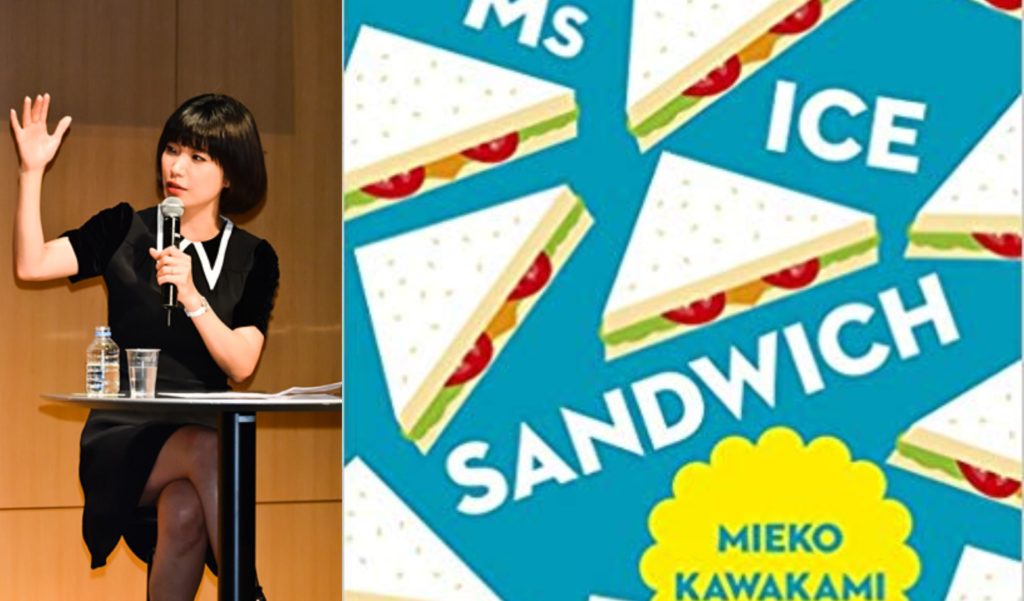

9. Mieko Kawakami (川上未映子)

Although not related to Hiromi Kawakami, Mieko Kawakami is another Japanese literary star you should consider. Her work even attracted the attention of Murakami who gushed about her on Literary Hub: “Like a tree can be counted on to grow tall, reaching for the sky, like a river can be counted on to flow towards the sea, Mieko Kawakami is always ceaselessly growing and evolving.”

Born in Osaka in 1976, Kawakami did not lead a privileged life. Instead, she grew up poor and had a strained relationship with her father. Although she started off as a singer-songwriter, in 2006, she turned to fiction, publishing her debut poem, Sentan de sasuwa sasareruwa soraeewa. In 2008, she won the Akutagawa Prize for her debut novel, Chichi to Ran (Breast and Eggs, translated by Louise Heal Kawai).

Why read Kawakami: In Breast and Eggs, Kawakami focuses on the working-class women of Osaka. The novella is characterized by their sassy, no-frills Osaka ben (Osaka dialect), rendered in street-wise Mancunian English by English translator, Louise Heal Kawai, giving insight into the lives of average Janes in Japan’s second largest city.

Recommended reads: Breast and Eggs, Miss Ice Sandwich (translated by Louise Heal Kawai)

Our nine writers’ collective work, which spans from the quirky and magical to the deadpan and realistic, reveals that there is no one literary style when it comes to Japanese women writers. All of these contemporary literary figures instead demonstrate that Japanese literature is indeed diverse and far from being just a gentleman’s club and it’s about time they get acclaimed on a global level as well.

Leave a Reply