Savvy Spotlight: Keiko Ochiai From Crayonhouse

One Woman's 40 Years Of Cracking Japan's Cement Ceiling

An interview with a woman who continues fighting Japan’s status quo through a small-turned-big store in central Tokyo.

For a woman who pens a minimum of two books and dozens of essays a year, runs a four-story bookstore and restaurant, manages a clothing brand, conducts human rights seminars and workshops across Japan, serves as a commentator on TV, and still manages to update her blog almost daily, Keiko Ochiai smiles a lot. She is also elegant in a typical Coco Chanel way, a minimalist extracting the best of simplicity, and an owner of the coolest hairstyle one could ask for. As we sit with her to chat about her work at Crayonhouse, the country’s oldest children’s books and organic restaurant that has now turned into a cultural center for information on human rights, we can’t help but think that if the thousand-armed Avalokiteshvara was incarnated into a human being, it would be no one else but Ochiai.

One of the most influential public figures in the Japanese media sector and a vocal supporter of Japan’s anti-nuclear and anti-war movement, Ochiai rose to fame in the late 1960s, during which time she worked as an announcer in charge of several programs, including several of her own. In 1974, she withdrew from the media sector to concentrate on writing, a career she still pursues today at the age of 72 after publishing over 130 books and essays on topics stretching from social problems to inspiring self-help stories.

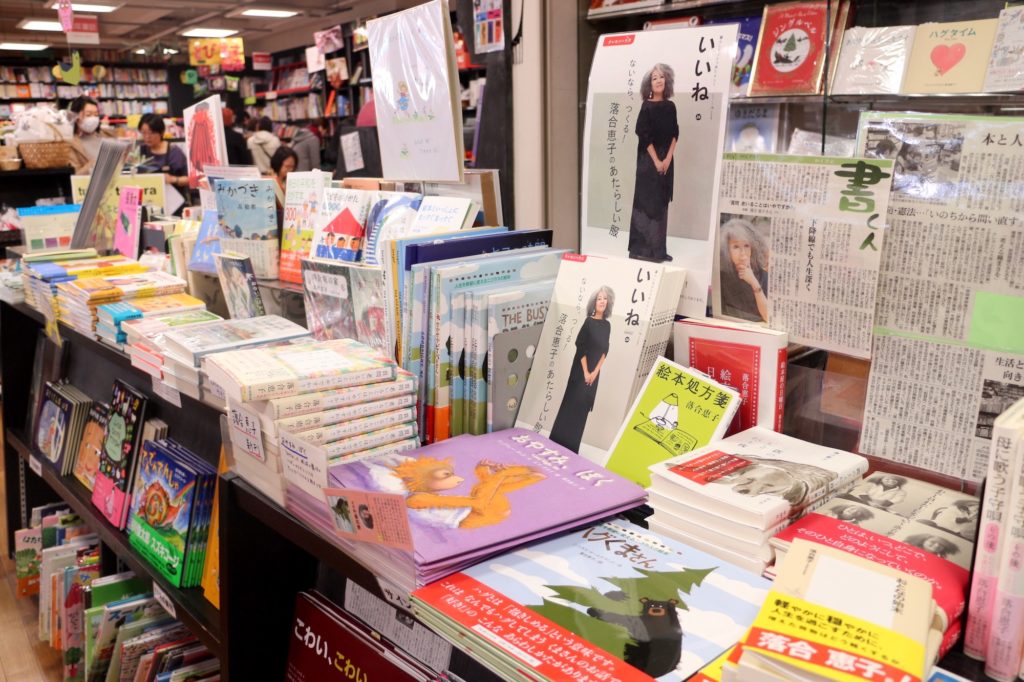

But the core of all her actions and principal beliefs — and the source of her energy — is Crayonhouse, which Ochiai founded in 1976. What started as a small children’s bookstore has now turned into a center for the millions of unheard voices in the Japanese and global minority communities, where they can gather and stand strong: from farmers selling organic food, to writers selling books on sensitive subjects, to fair-trade jewelry and cosmetics producers.

We catch up with Ochiai at her office in Omotesando to learn more about the history of Crayonhouse and the woman behind it.

First things first. Tell us about your business at Crayonhouse. How did it start?

Crayonhouse, which marked its 40th year anniversary last year, started as a children’s bookstore. Our focus on children derives from my belief that a society that is kind to children, that thinks about the happiness of future generations, is a society where anyone can live happily. Starting off with this belief, our business has now extended to all those who have been somewhat marginalized in their societies. Crayonhouse represents two interrelated themes, life and human rights. We also go by the motto, “If it doesn’t exist, create it yourself.” There was no children’s bookstore in Japan when we started and also no organic restaurant.

Crayonhouse has four floors: a children’s bookshop on the 1st; toys on the 2nd; cosmetics, clothes and books for women on the 3rd, and an organic restaurant and market at the basement floor.

Why “Crayonhouse”?

Oh, that debate lasted for some time and we had quite a few arguments about it (laughs). But I thought that it’s crayons that kids take up to draw something for the first time, not pencils, pens or whatsoever. I wanted kids to paint their own original and colorful pictures. The word ‘house,’ on the other hand, signifies a place you belong to; a place where people gather. So Crayonhouse represents a place where people from different backgrounds can come together, as an extended family.

You used to work as an announcer at Nippon Cultural Broadcasting. How was it back in the day?

At first I wanted to be a journalist and I applied for a number of major media companies, but I failed most of them. This was largely due to the fact that I was born out of wedlock, which back in those days was enough of a reason to be turned down institutionally. Many companies considered a woman, who doesn’t have a registered father, “inconvenient,” and as a result I couldn’t get through the final selection process. After a number of trials, one broadcasting company offered me a job as an announcer, which back in the 1960s, was pretty much the only media job women could do. I told them that I wanted to be a reporter, but that was a “male” job. So I thought, well, if that’s the closest I can get to the media sector, let’s go for it.

Did you encounter any obstacles as an announcer because of being a woman?

Oh my, there was nothing but obstacles (laughs). My company was relatively liberal but women were for the most part treated just as assistants. When I expressed my opinion — because that’s what I’ve been doing ever since I started talking — male staff began alienating me, saying that it was difficult to work with me. I was taken down from the program a number of times. We have a glass ceiling now, but back then it was a cement ceiling, right above our heads.

We have a glass ceiling now, but back then it was a cement ceiling, right above our heads.

So you quit to become a writer?

Yes, what I really wanted to do was to write, but I also wanted to climb to a position which allowed me to freely talk about violation of human rights and social taboos everyone ignored. I wanted to do this through writing rather than through talking. I began writing essays while I was still an announcer and they became quite popular and I thought it was about time to focus on writing.

As a child born out of wedlock, you have experienced a fair share of social discrimination. Do you think that Japan has changed since the time you were growing up?

Some things have changed for the better, some not so. Back in the days, people used to call us shiseiji (love child) or tetenashiko (a child without a father) and hichakushutsushi (illegitimate child), but we now have the less-discriminatory kongaishi (a child outside of marriage). The society is still built on the idea that all children should be a product of marriage, but overall I think we have become more liberal in this respect.

I think that one of the greatest human pleasures is the right to oppose the authority and fight for your rights and beliefs.

On the other hand, discrimination against minority groups and foreigners is still prevalent. When Japanese say “gaikokujin” (foreigners), they only think of white, blue-eyed folks. The rest of the foreigners are for the most part ignored or looked down on. So there’s still a long way to go.

You are also a very vocal activist. Why do you keep fighting for human rights?

Inequality is one of the things I detest the most. Through my work I want to break four social stigmas: racism, sexism, ableism, and ageism. I think that one of the greatest human pleasures is the right to oppose the authority and fight for your rights and beliefs. Here at Crayonhouse we organize monthly meetings where we can exchange our opinions on nuclear power plants or the Japanese government’s loss of pacifism. We should not be afraid of expressing our opinions and I would like to make Crayonhouse a place where you can freely do that.

You’ve always said that you want to be the voice for the unprivileged. When do you have a feeling of accomplishment in doing so?

I rarely have a feeling of accomplishment (laughs). But to give you an example, in 1985 I wrote a book called The Rape, which is based on women’s testimonials of suffering sexual misconducts. At first, it was difficult. One weekly magazine accused me of writing porn — and they hadn’t even read the book! Rape has long been relished as an entertainment in this society. Victims could not speak up. But, now 30 years later, I feel that my book helped bring the discussions upfront, and more and more men began thinking from another angle: what if the victims were their wives or daughters? People’s perspectives about the subject have changed to a great degree.

Unfortunately, however, most news reports on rape are done only in cases when they involve people from high-end societies. You will hear in the news that university students gang raped a woman, but it’s news only because the universities are prestigious. Yet, it happens everyday. It is not important which university the criminals are from; it is crucial to publicly and openly accuse such actions as violations of human rights. So sometimes I feel that I have advanced one step forward but then I get quickly drawn back to the same position.

As a role model for many, do you have any message for our readers?

I don’t think people should have role models. When I was young, I, too, tried to find someone that can be my role model. But I realized that although you can consider someone else’s achievements and words inspirational, it’s better to live your own life and be yourself, rather than choosing and following the footsteps of someone else. A message? I would advise women to have at least 10 minutes everyday to be alone and energize themselves. This might give you a different perspective and new purpose in life. I also like Angela Davis’s words, “Walls turned sideways are bridges.” Someone told me that I look like her because of the similarity in hairstyle (laughs).

How do you manage to find time for everything you do?

People often ask me what gives me so much energy to fight and do everything I do, and I say, “I treasure the time when I’m alone.” I’m always in a rush, but it’s important for me to have a bit of time alone everyday — you know, just to look up the sky or watch the small seedling at my house grow. That is what gives me energy, I guess.

Savvy Spotlight is a monthly feature introducing foreign and Japanese women at the frontline of what’s cool, unique and interesting in the city. If you have anyone in mind you would like us to interview, leave us a comment below with your recommendations!

Comments

Leave a Reply

Crayonhouse

Crayonhouse is an organic restaurant, children's bookstore and organic specialty goods shop based in Tokyo's Omotesando and Osaka's Esaka.