As Reconstruction Progresses, 3.11 Survivors Find Hope in Telling Their Stories, Embracing the Past

Visiting The Affected Areas And Learning From Their Stories Now May Be The Best Way We Can Help

While Tokyo is preparing for the 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games and Tohoku's reconstruction proceeds slowly but steadily, most tsunami survivors carry on living day by day unable to forget the past. For fear of society's memory loss and as a way to cope with their own unhealed trauma, however, many are gradually beginning to address the memory of that dreadful day. One way we can help them move on is by continuing to visit the area, listen to their stories and learn how to protect ourselves in the future.

“I apologize for leaving the room,” he said after a long pause.

“I have learned to carry on with my daily life, but sights like this bring the flashbacks back. It’s the voices, mostly, that I can not forget. Friends, neighbors, relatives seeking help…and the sound of our own voices, on the other side, begging them for forgiveness that we couldn’t save them.”

We sat quietly in the moving car unable to say a word. We didn’t know what words or sign of emotion could possibly help him feel better, a man who had lost so much more than just his entire house in the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami eight years ago. There was no way we could understand his pain, nor even imagine it.

The man was our driver for the day and we were in Iwate Prefecture as part of a reconstruction familiarization trip, touring several coastal cities that were most heavily damaged by the 3.11 tsunami. Shortly before he opened up to us, we were at the former Taro Kanko Hotel in Miyako city, a building that was heavily scarred by the tsunami. We were there watching documented footage of the tsunami, standing in the exact same room it was filmed from. Before we knew it, he had left the room in silence.

Retelling the past

On March 11, 2011, an estimated 17-meter-high tsunami reached the fourth floor of the six-story hotel, leaving nothing but a bare steel frame and pillars on the first and second floors. The quake struck at 2:46 p.m., before the check-in time when fortunately there were no guests. The hotel owner, Yuki Matsumoto, was on the sixth floor, watching the tsunami come in a series of waves. The first tide hit and minutes later came the second, far higher, furiously engulfing everything in its way: houses, fishermen’s boats, shops, buildings…memories. Matsumoto rushed his staff to evacuate toward the hill behind the hotel and impulsively switched the camera on.

Taro Kanko Hotel before the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami.

Taro Kanko Hotel after the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami.

In just a few minutes, the town was almost entirely wiped out, resembling a massive lake filled with broken wood piles, mud and debris. The several-minute-long footage ends with Matsumoto pointing the camera to the roof, ending it abruptly. He was finally on his way to the hill himself, managing to evacuate at the last minute.

Under a collective agreement between survivors and municipal politicians, the former hotel was saved from destruction and today remains one of the very few buildings preserved as they were at the time of the tsunami. It was done so to serve as an educational facility, welcoming visitors to learn about the disaster from a first-hand perspective and see the footage of the tsunami.

Scarred as they still are, the residents of this small town are doing this with a single thought in mind: to pass their experience to the next generation in hopes that if one day the same thing happens, they would know how to save their lives. By doing this, the survivors also found their own way to cope with their memories.

“The only way to survive a disaster is to learn from it,” says Kumiko Motoda, our Miyako city disaster prevention tour guide. “Living in an area like this means that we’re living next door to a tsunami. If an earthquake strikes, run to higher ground and save yourself. This is what we teach our children here.”

‘The only way to survive a disaster is to learn from it.’

Indeed, a three-time massive tsunami survivor, Miyako is a town that was well prepared for a natural disaster. In 1896, a magnitude 7.6 earthquake caused a 15-meter-high tsunami, killing or leaving missing 1,859 people. In 1933, a more intense quake — magnitude 8.3 — left 911 casualties. The strongest quake on March 11 — magnitude 9.0 — triggered a 16-meter-high tsunami. Yet, the casualties were limited to 181, including 41 missing to date. This, explains Motoda, is the result of a continuous retelling and learning from previous disasters.

For Motoda, however, becoming a guide and choosing to pass on the memories of that day to future generations, was also a way to cope with her own trauma of that day.

Kumiko Motoda, in the blue jacket, talks to participants at a local disaster prevention tour in November 2018 in Miyako, Iwate Prefecture.

As soon as the quake struck, she acted subconsciously, remembering what she was taught since childhood: to run and save her own life. Praying that all her family members and friends were doing the same, she kept running and ultimately survived. But when the waves eventually subsided, her aged mother-in-law was nowhere to be found.

“We are still searching for her,” she says quietly. “Would I have been able to save her if I had returned back home first, I don’t know. I will never know. This is something I have to live with for the rest of my life; something I will never have an answer for. But being able to tell this story and believing that it helps others prevent future misfortunes helps me move on. I think I can find peace with myself.”

Becoming a Kataribe

“I couldn’t do any volunteering work after the tsunami,” says Aya Yokozawa, a guide and a Rikuzentakata-native, known as a kataribe — locals who are now openly retelling and sharing the stories of the tsunami.

“I just couldn’t bear the thought that I may find the body of a person I knew, a classmate or an old friend. For years, I didn’t want to face the reality and I didn’t do anything to help — which bothered me immensely. I was just emotionally paralyzed.”

Working in Tokyo at the time of the disaster, Yokozawa learned about the tsunami from the news. The endless waves of water engulfing areas where she used to play as a child looked just too unreal through the screen. Rikuzentakata, a small town famous for its beautiful white sandy beach before the disaster, was completely wiped out in just a few hours, leaving 1,604 dead and 202 still missing to date. It was the worst affected city in Iwate Prefecture.

“This used to be a city,” she tells us pointing at the ground. We see nothing but sand surrounding us, standing confused trying to picture a city here. It had all been wiped out, cleared and had since been elevated by some 10 meters above where it used to stand. The local government is planning to build a national park, a beautiful green space that would replace the grey sight that’s currently here.

“This used to be a city.” Rikuzentakata now, nearly eight years after the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami. The ground has been elevated by 10 meters and construction of a national memorial park is currently underway. Photo was taken in November 2018.

Yokozawa takes us to the next destination, the former Rikuzentakata Kesen Junior High School, which was engulfed by the tsunami. Luckily, all of the nearly 100 students and their teachers at the time were saved, thanks to their quick decision to run to the highest place possible as soon as the quake struck. The teachers knew that with a quake of that scale, the tsunami would be massive. The students and teachers disregarded the evacuation manual — which taught them to escape to the hill nearby — and instead ran further and higher. It was this decision that saved their lives.

“This building is one of the only four in the city that have been preserved as they were on the day of the tsunami,” Yokozawa says. “The only condition to preserve them was that no one had died in them. No one could bear to keep a building where people had vanished.”

The former Rikuzentakata Kesen Junior High School is one of the only four buildings in the city that remains preserved. The reason why it remains preserved is that no fatalities were recorded there.

Several years after the tsunami, Yokozawa got back on her feet, bid goodbye to her work in Tokyo and moved back to her hometown, this time no longer fearing the past.

“I knew that I had to face the reality in order to move on with my life. I couldn’t bear doing nothing anymore, I couldn’t bear hiding,” she recalls.

Aya Yokozawa, far right, talks to the media at a reconstruction tour in Rikuzentakata, Iwate Prefecture, organized by Marugoto Rikuzentakata, an NPO she now works for.

Upon her return to Rikuzentakata, Yokozawa joined an NPO, Marugoto Rikuzentakata, through which she now organizes tours in the city under the concept of “Rikuzentakata: Past, Present and Future.” The tours, offered in English, Tagalog, Spanish and Chinese by other kataribe, long-term foreign residents who have survived the tsunami, aim to show visitors what the city was before the disaster and how it will develop when reconstruction is finally completed.

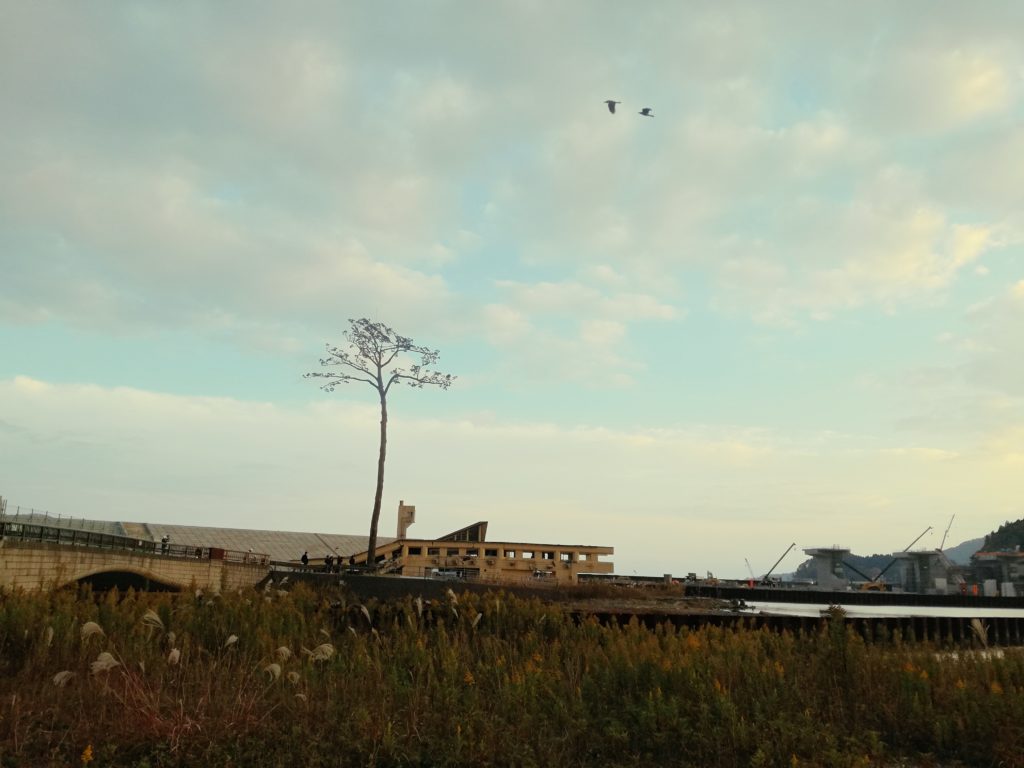

“I think people are finally beginning to find ways of coping with what happened, and while many still prefer to avoid talking about the past, others are finding some sort of healing in the idea of sharing. I think that people are also afraid that if we don’t speak up now, everything will be forgotten with time,” she says as we stand near the last stop for the day, the Miracle pine tree, or Kiseki no ippon matsu, the sole tree that survived the tsunami among over 70,000 that were washed away.

The Miracle Pine Tree survived the tsunami for a short time in 2011. With the efforts of locals and donations from other prefectures and countries, the tree was preserved in its current form. It stands next to a former youth hotel that was heavily damaged by the waves. The hostel is now one of the four buildings that remain preserved as they were at the time of the quake and tsunami. As it wasn’t operating at the time of the disaster, there were no reported casualties. The miracle pine tree, or Kiseki no Ippon Matsu, stands as a symbol of the city’s strength and willingness to survive. Photo taken in November 2018.

“When this whole land turns into a beautiful park, the society will gradually forget (what happened here). I want people to see how much we’ve been through, but also how far we’ve come,” Yokozawa says as she hands us a small farewell gift — postcards of Rikuzentakata: an elderly woman baking bread, a fisherman catching oysters, a man crafting wood — and the sole pine tree, still standing.

Looking ahead

A month from now on Japan will be marking the eighth anniversary of the March 11 disaster. While it has taken a very long time to even begin thinking of the future, and for many a full recovery will never take place, Tohoku is slowly but gradually moving on.

The former Taro Kanko Hotel has since last year found itself a new and safer location under the name of Nagisatei Taro-An, a modern inn built on a hill overseeing the ocean. It has fewer rooms than before, but it offers visitors a place to relax, take time slowly and perhaps even take a moment to appreciate life as it is. The place also serves as a symbol for owner Matsumoto that guests will return to the area — and it seems that they are beginning to do so.

© Photo by Nagisatei Taro-An

© Photo by Nagisatei Taro-An

Infrastructure is also recovering. The JR Yamada Line, a local train running along the Sanriku coastline, will resume full operations between Miyako and Kamaishi cities, under the name of Kita-Riasu Line, operated by Sanriku Railway Co., from March 24. The 55.4-kilometer section was heavily damaged in the tsunami to the extent that the then-operating company, JR East, suggested in 2012 that the section needed to be forgotten. A symbol of the region, however, and a popular scenic route for tourists and locals alike, residents’ efforts helped preserve and restore it.

Last but not least, the world will also set eyes on Kamaishi, a port city in the prefecture, when the 2019 Japan Rugby World Cup kicks off this September. The only Tohoku city of the 12 hosts throughout Japan, Kamaishi now proudly stands by its newly constructed Kamaishi Recovery Memorial Stadium where Fiji will play against Uruguay on September 25 and Namibia against Canada on October 13. Built on the premises of a former school washed away in the tsunami, the stadium is now a new symbol of recovery and a ray of hope for the locals who are anticipating the games as the first major international event ever taken place in their hometown.

The Kamaishi Recovery Memorial Stadium as seen on Nov. 2018. Photo by Alexandra Homma

Slowly but steadily, damaged but still standing, Tohoku is looking forward without forgetting the past — past that people still need to embrace and retell in order to see the future.

To join a disaster reconstruction tour and learn about the past, present and future of the affected areas via real disaster survivors, check the following information:

- Marugoto Rikuzentakata (Rikuzentakata, Iwate Prefecture). For inquiries and bookings, see here or contact the organization at info@marugoto-rikuzentakata.com.Tours are available in English, Tagalog, Spanish and Chinese. Cost: ¥6,000 per person for up to two hours.

- Disaster Prevention Tour (Taro District, Miyako city, Iwate Prefecture. Includes a visit to the former Taro Kanko Hotel). For inquiries, see here or call 0193-77-3305. Cost: ¥4,000 per group (From one to 40 people, approximately one hour course).

- Kamaishi Tourism Volunteer Guide (Kamaishi, Iwate Prefecture). For inquiries and booking, contact kamaishi-kankou@taupe.plala.or.jp or call 0193-22-5835. Cost: ¥3,000 for a group of up to 40 (3-hour course).

- For sightseeing recommendations, events and suggested itineraries in Iwate Prefecture, see visitiwate.com

Lead photo: A Rikuzentakata tsunami survivor looks at a missing person list at an evacuation shelter in Rikuzentakata on March 23, 2011, Japan. On 11 March 2011, an earthquake hit Japan with a magnitude of 9.0, the biggest in the nation’s recorded history and one of the five most powerful recorded ever around the world. Within an hour of the earthquake, towns which lined the shore were flattened by a massive tsunami, caused by the energy released by the earthquake. With waves of up to four or five meters high, they crashed through civilians homes, towns and fields. Credit: RyuSeungil, iStock.

Leave a Reply