A Beginner’s Guide to Japanese Lacquerware

Urushi and You: A Natural Treasure That Lasts

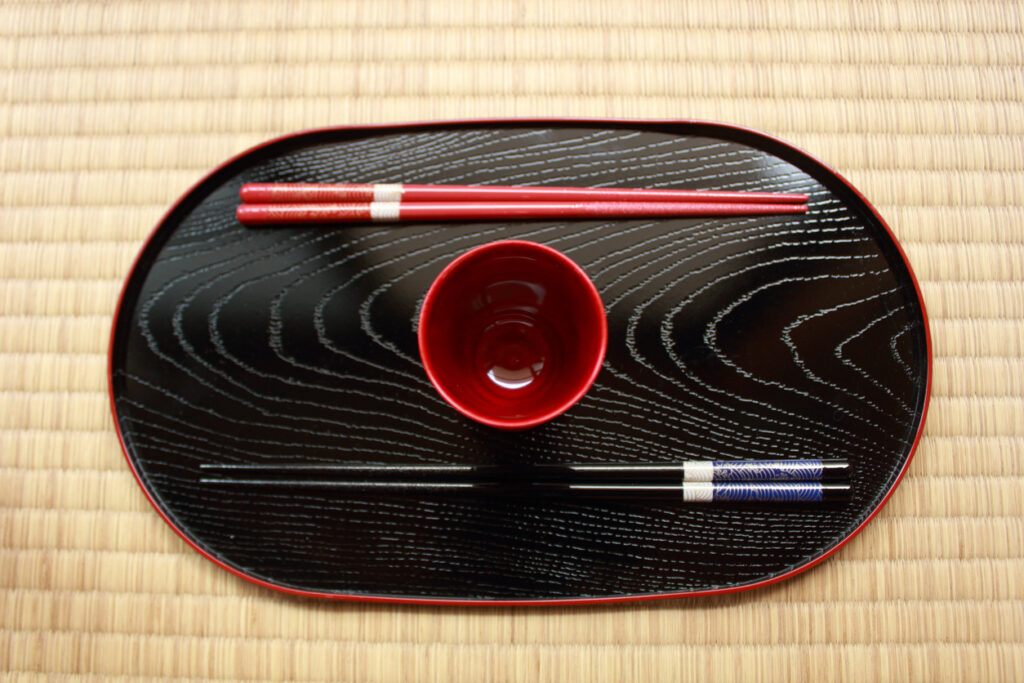

While ceramic dishes and metal cutlery are standard fare, there’s something very satisfying about having a bowl that will grow and change as you do.

While there are scores of different traditional handicrafts found across Japan, one with the longest history of all is urushi, or lacquerware.

What is urushi?

Urushi, or lacquer, comes from the varnish made from the sap of the urushinoki, better known in English as the Japanese lacquer tree or Japanese sumac. The items made from and with this lacquer are known in Japan as either urushinuri or shikki.

The history of lacquerware

Lacquer has been used in Japan since the Jomon period, anywhere from 15,000 to 2,300 years ago. During that time, it was mainly used as an antiseptic or adhesive, but over time it became a staple used in both functional and decorative items.

Everything from wooden pencils to everyday use soup bowls, hair combs, and even armor and coffins have been made from lacquerware. It is mainly applied to carved wooden items, but urushi is also used on metal, glass, fabrics and even plastics.

Be careful

The Latin name for the urushinoki contains a hint as to the main problem with lacquer itself — Toxicodendron vernicifluum.

The liquid sap from these and other trees in its family contains urushiol, the same compound in poison ivy and poison oak that cause severe rashes and potentially fatal allergic reactions. In Japanese, the rashes are known as urushi kabure, or urushiol induced contact dermatitis.

While lacquerware products generally don’t cause reactions in users, while taking part in a lacquerware tutorial, my instructor informed me that those who have severe allergies to poison oak and so on might want to appreciate lacquerware from a distance, just in case.

Famous styles

As with most things, there are regional differences to shikki across Japan. Given that the sap is a natural component, knowing when and how to collect it, the quality and viscosity of the substance itself, as well as how long the lacquer will take to dry in a given area varies greatly. This knowledge comes from years of experience — often generations of it — and as such, areas with the longest established traditions of producing urushi tend to also have some of the finest items available.

There are about 30 well known lacquerware brands available today, each with its own special techniques and designs. Here are some of the most commonly known types.

- Daigo Urushi: A type found close to home that comes highly recommended is Daigo urushi, from Ibaraki prefecture. The town of Daigo is the second largest producer of lacquer in all of Japan, and the pieces found here have this weight to them that makes them both beautiful to look at, but also sturdy enough for daily use.

- Negoro Urushi: One of the most famous and heavily copied styles is Negoro urushi, which comes from the former Izumi province (modern day Osaka area). This style sees items first painted with black lacquer, which is then covered by layers of red. Through use, the red begins to wear away, leaving a distinctive black area behind. A lot of antique lacquerware from this region looks like it’s damaged, but that’s actually intentional from years of use. This is also the most commonly faked type of lacquerware, especially in online auctions — so be careful.

- Tsugaru-nuri: In northern Japan’s Aomori Prefecture, you’ll find Tsugaru-nuri which is famed for its mottled effect. This design is created by layering different colored lacquers over one another and is believed to have been developed in the 17th century.

- Wajima-nuri: Ishikawa Prefecture is where Wajima-nuri was developed in the 15th century. It’s most famous for its durable undercoating over zelkova wood. This coating is made from layers of urushi mixed with keisodo (diatomaceous earth, similar to pumice powder). It’s also where Yamanaka-shikki developed — this includes sensu jibiki (heavily ridged woodworking designs), shudame-nuri (lacquer layered over a vermillion base) and koma-nuri, a unique ringed pattern based on Japanese spinning tops.

- Johana Urushi: Johana urushi comes from Toyama Prefecture and it’s renowned for both its white lacquer and its use of maki-e and mitsuda-e (gold and lead powder, respectively). Personally, I find it to be the most modern and artistic of urushi styles, so if you want something more contemporary, this is your best choice.

You can find these and other styles in most department stores, but if you’re looking to support local artists, Japanese online shopping sites like Creema and Minne are good options to try.

Recognizing good quality

While you can find lacquerware items in Daiso and other ¥100 stores, there are extreme differences in quality that you should consider before buying anything urushi-based.

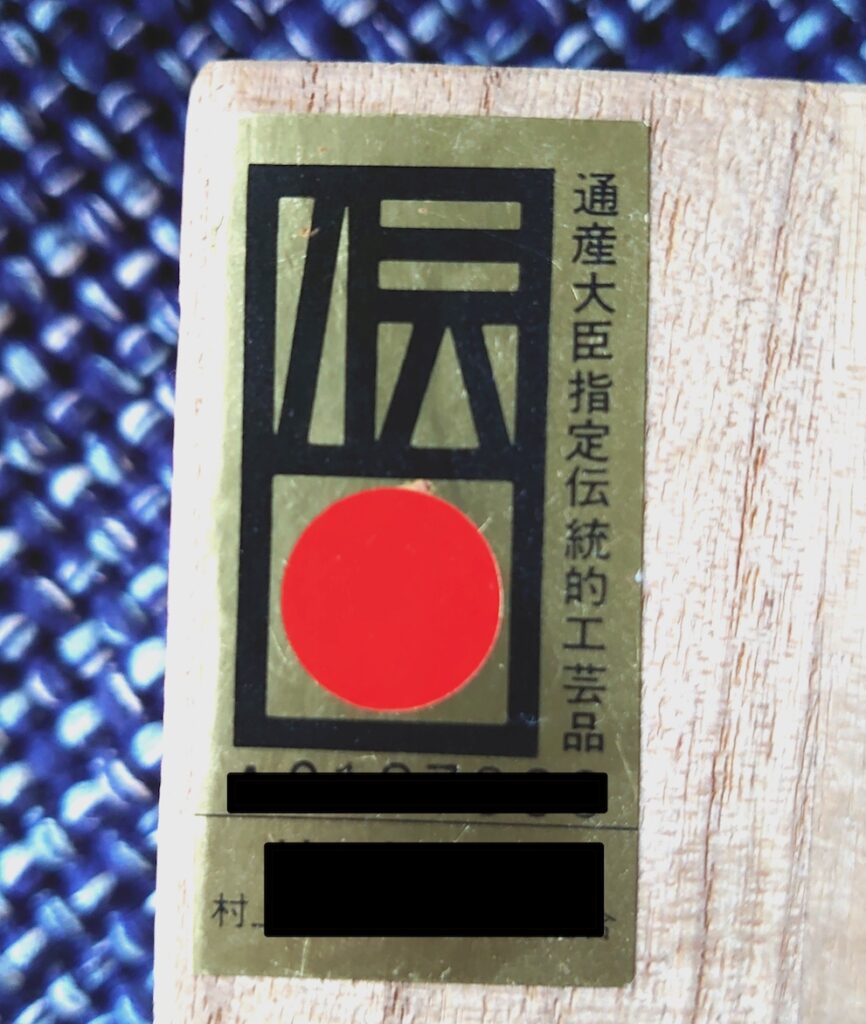

The easiest way to make sure you’re getting something of quality is to buy it directly from an urushi artisan, but that isn’t always an option. Products that are recognized as authentic Japanese handicrafts will have the associated seals and paperwork included in the box or on the item itself. You can find these at made-in-Japan specialty shops such as Japan Traditional Crafts Aoyama Square or The Cover Nippon.

If you’re looking for high quality and durability, wood based items are your best bet. Check for any labels on the item — it should be marked “天然木” (tennenboku, or natural wood) or indicate the type of wood used. The most common is keiyaki, or Japanese zelkova.

The next thing to check the label for what type of varnish has been used. The three most common are:

- 漆 (urushi)

- カシュー 油性漆塗 (cashew oil lacquer)

- ウレタン樹脂 (urethane resin)

Generally speaking, if it’s not made with actual urushi, then it will be cheaper. Cashew oil and urethane resin will be easier to maintain on a daily basis — many of these items are dishwasher and microwave safe — but they won’t age or change as real urushi products will.

The perks of lacquerware

Being more eco-friendly is the goal of many, and that makes lacquerware a good, sustainable option. Traditionally made lacquerware is tree sap layered over wood — there are no harsh chemicals involved in the production or creation of these items. They’re also great at insulating or keeping foods warm. Wood heats internally, and as such, urushi bowls are very popular for soups and Japanese curries, too.

Not only is lacquerware beautiful, but it’s also an extremely good investment: these items will last longer and become more beautiful with time.

Many shikki producers say that the owner is the one that makes lacquerware’s true beauty come through. By use, the layers of the urushi change — they thin or wear away, exposing new layers, or they become shinier from constant touch. This is how Negoro types evolve, as mentioned above, and also how some antique or museum displayed pieces seem glossier than those available brand new in shops.

Lacquerware care

If you have opted for real, traditional urushi items, then you’ll need to care for them properly to get the most bang for your buck.

Don’t let your shikki get dried out or overly exposed to UV rays. If you prefer to display your collection rather than use it, make sure that it’s not in direct sunlight for several hours a day. Most traditional items come in a wooden box with paper that can be wrapped around it to protect and keep it humid. If not, storing the shikki in a cupboard with solid doors or a relatively humid place is enough to keep it in good condition.

If you do want it for everyday use, then there is one hard and fast rule: go old school. This means do not put your lacquerware in the dishwasher, microwave, toaster oven or use it with hand mixers or any type of sharp implement whatsoever. If you need to wash it, use a mild, environmentally friendly detergent. Do not — never, ever — let it soak in the sink. While urushi should never dry out, it should also never be soaked completely. After gently washing it, dry it with a soft dish towel and put it away until its next use.

© Photo by Hilary Keyes

© Photo by Hilary Keyes

Properly cared for, urushi can and will last for decades. If you choose an item that is made from wood and coated in proper urushi, you will have a treasure to last a lifetime.

Do you need to be careful of the temperature of the food or liquid that you put in the. Lacquerware- I.e. if it was a teapot, can it take boiling water? Also is there any type of treatment for the wood that helps it from drying out, like mineral oil?